Dutch artist Jan Toorop’s The Ferryman (1895)—based on a poem about a ferryman who pursues a mysterious woman—is an unusual work of art. Drawn in ink and gouache on four pieces of tightly glued boxwood, it was meant to be carved and printed as a wood engraving. Although it was signed by the artist in reverse, so that his signature would read correctly, it was never finished. “We thought it was part of this object’s story, to show the edges of the woodblock,” said Edouard Kopp, the Maida and George Abrams Associate Curator of Drawings at the Harvard Art Museums. “As a drawing it’s resolved, but as a print it was never finished.”

The Ferryman is one of about 40 drawings in the new exhibition Flowers of Evil: Symbolist Drawings, 1870–1910. Though it is not a work on paper like many of the other objects in the gallery, it fits in seamlessly with the theme of the exhibition.

Active in Europe and the United States, symbolist artists were not unified by technique or style. Instead, they shared an interest in making the invisible visible. The movement, which originated as a literary phenomenon, formed an important bridge between impressionism and modernism. Symbolist artists used the unique properties of drawing (alongside other media) to confront and make sense of a chaotic and complex world at a time when Western society experienced rapid change and dramatic urbanization.

The symbolists attempted to represent nature as a mysterious force in need of translation, and as a means of religious or spiritual connection. Piet Mondrian’s Farmstead (1906–7), a large charcoal and chalk landscape drawing, features animals that look ghostlike. Mondrian’s relatively realistic portrayal of the natural world will likely surprise viewers who are familiar only with his (later) abstract paintings.

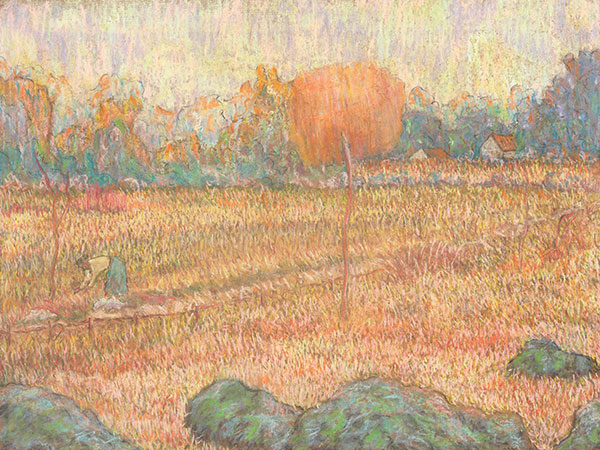

Paul Gauguin’s Parahi te marae (There Is the Temple) (c. 1892) is a vivid watercolor of an imaginary marae, a sacred enclosure intended for ritual sacrifice, derived from an ancient religion in the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia. The serene landscape invites comparisons with Claude Emile Schuffenecker’s Landscape with an Orange Tree (1889–91), whose velvety pastel strokes depicting the tree, a field, and an individual in the foreground give a luminous effect and a somewhat livelier atmosphere than that seen in Gauguin’s work.

Schuffenecker and Gauguin coined the term synthétisme to refer to their aesthetic approach, which held that art should reflect an artist’s feelings about his subject while also experimenting with form and color. In using anti-naturalistic colors, their works epitomize the symbolist artistic approach that strove to de-familiarize reality as a way to connect with what lies beyond worldly appearances.

As symbolists tried to negotiate the pressures that the fast-changing world exerted on the human psyche, many focused their attention on society. For some, there was hope of regeneration, while for others, like Belgian artist James Ensor, society was corrupt and decadent. Ensor’s colorful crayon and ink Temptation reflects this view, with its image of two beautiful women surrounded by an unsettling crowd of men in monstrous masks.

On the same wall as Temptation, other drawings explore symbolist artists’ use of literary works as source material. These works tended to be loosely evocative instead of straightforwardly narrative. British artist Aubrey Beardsley’s black and white The Dancer’s Reward, for “Salome” (1893), an illustration for an Oscar Wilde play, is both extremely refined and decadent. In the drawing, the biblical character Salome grasps the severed head of John the Baptist, which drips blood. “The drawing showcases a connection between death, sexuality, and touch, and a typical symbolist interest in the relationship between the senses,” Kopp said.

A larger story being told by Flowers of Evil is that of the breadth of the museums’ drawings collection. With more than 12,000 drawings that date from the 14th century to the present—including many examples of works in varied states of progress, such as The Ferryman—the collection is unparalleled among American university museums. “Our 19th-century holdings are so deep that there are works we rarely show,” Kopp said. Because the collection is so broad he was able to include a section in Flowers of Evil that highlights the work of artists who were important precursors of the symbolists, such as Gustave Moreau, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and Rodolphe Bresdin.

Standing in front of Moreau’s Galatea (1896), depicting the mythological sea nymph Galatea and a lustful Cyclops in a richly hued and surreal landscape, Kopp noted that the drawing is part of the museums’ esteemed Winthrop Collection, a bequest to Harvard that dates back to 1943. Flowers of Evil, Kopp said, “is a great opportunity to present works that we haven’t had the chance to display very often, but that are very important.”

Those interested in viewing other works from the museums’ extensive drawings collection can arrange to visit the Art Study Center. Appointments can be scheduled here, and walk-ins are welcome on most Mondays, from 1 to 4pm.