This year will mark the second iteration of SITSA. The workshop builds on the Summer Institute for Technical Art History (SITAH), which was initially developed and led by New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, from 2012 to 2016. Both have been funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which counts among its many aims the support of productive collaboration between practitioners of art history and art conservation at all stages of their careers. (SITAH was itself inspired by Yale University’s Summer Teachers’ Institute in Technical Art History, funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.)

“SITSA provides us an opportunity to help new generations of curators and art historians learn how to engage with conservators and scientists in a more informed and nuanced way,” said Francesca Bewer, research curator for conservation and technical study programs at the Harvard Art Museums and director of the workshop. “These immersive two weeks give participants unusually close access to artworks, technical tools, and vocabulary—a modeling of the types of research methodologies that we believe are essential for emerging curators and museum professionals as well as university-based scholars.”

Collaboration is essential in this work, and thus team building is seen as an invaluable goal of SITSA. (To this end, participants also live together in Harvard housing for the full two weeks.) In addition, because participants are placed in conversation with individuals who are more established in their careers, it has an even broader benefit for the field.

Bewer draws heavily on the expertise of staff in the museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies to develop and teach the curriculum. She also collaborates closely with curatorial staff and colleagues from across campus, as well as from other institutions.

Besides the Harvard Art Museums’ teaching team, SITSA project assistant Alexandra Gaydos and Jordan Koffman, a student assistant and intern for the museums’ Materials Lab, have been essential with preparations for the 2018 workshop.

Premier Training Ground

The Harvard Art Museums’ history—and innovative present-day character—make the institution an ideal home for SITSA. The Fogg Museum (one of the Harvard Art Museums’ three constituent institutions) was the first purpose-built structure for the specialized training of art scholars, conservators, and museum professionals in North America. As early as 1911, Edward W. Forbes, the museum’s director from 1909 to 1944, characterized the institution as a “laboratory for art” and a place to offer students exposure to inspiring teachers and genuine works of art. A pioneer of art conservation, Forbes also founded the country’s first scientific research and conservation laboratory at an art museum, a precursor of the Straus Center.

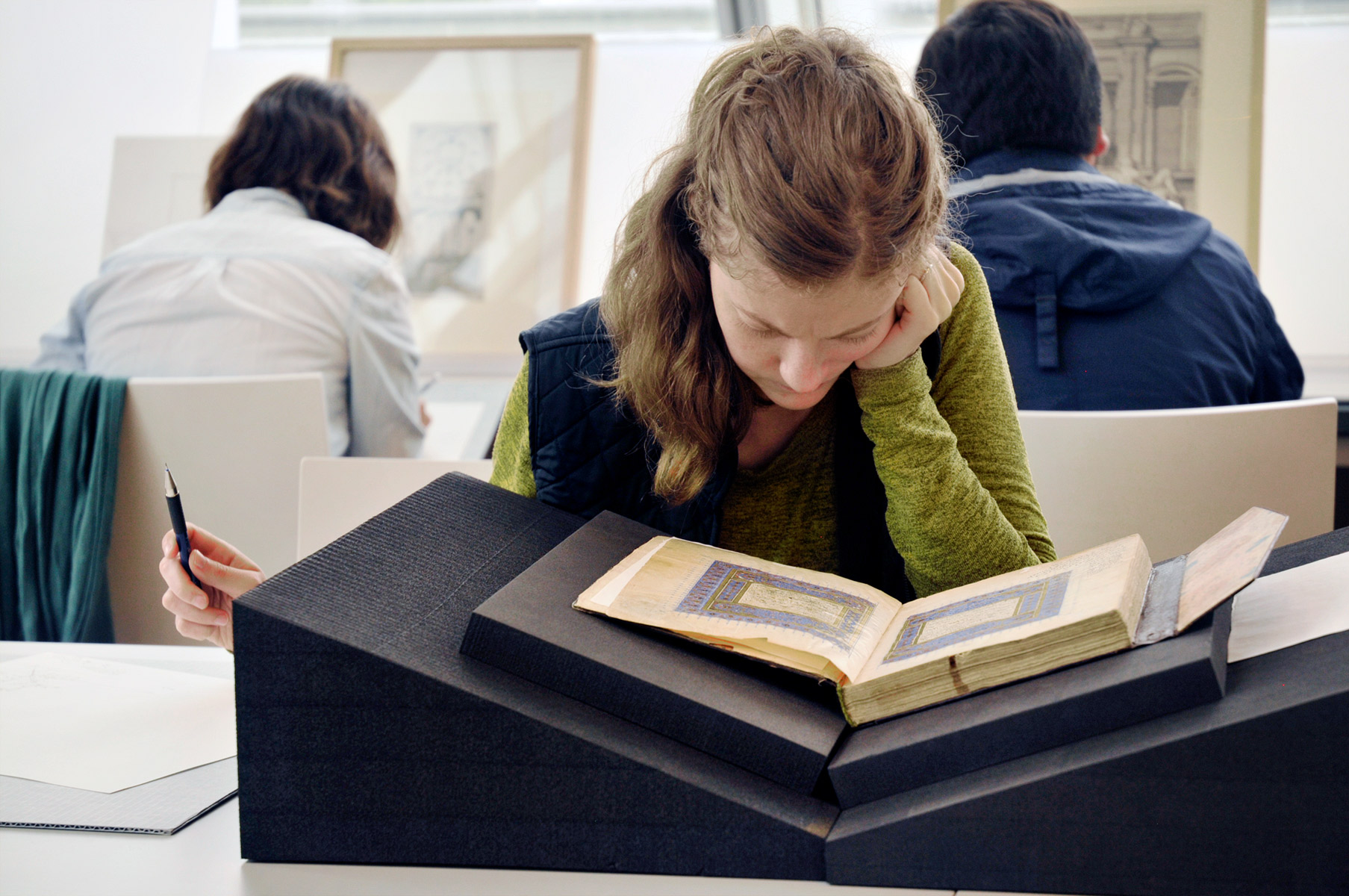

The 2014 renovation of the Harvard Art Museums brought Forbes’s vision and the Fogg’s institutional history into sharper focus, with the incorporation of in-house research centers and teaching spaces in which regular, collaborative conversations occur under the same roof. These include the Materials Lab, an environment for art making as a means of learning, and the Art Study Center, dedicated to the sustained viewing of original works of art. SITSA utilizes both of these spaces, as well as the Straus Center—and of course, the museums’ galleries—to expose participants to interdisciplinary engagement with art.

Multifaceted Experience

The theme of last year’s workshop—translation—focused on a range of interpretations, including the transfer of designs from concept to completed work, visual and verbal representations of artistic processes, and the analysis of technical and material evidence in physical objects. Students were invited to choose a work of art in the collections that would serve as inspiration for various hands-on translation exercises. Building on their greater technical understanding of materials and processes, students also took part in close technical examinations of these objects with conservation staff (aided by scientific equipment), and practiced peer-to-peer teaching in synthesizing what they learned. By translating their chosen works into different media, the students became more mindful of artistic choices and of the dynamic relationships between materials, tools, and makers.