While it’s been nearly a century since the founding of the Bauhaus—the influential school of art, architecture, and design that opened in Weimar, Germany, in 1919—its continuing impact is unmistakable.

That legacy is made abundantly evident through the Harvard Art Museums’ Bauhaus Special Collection, an online resource of more than 30,000 objects related to this pioneering school. For the past two years, the website has virtually placed the museums’ Bauhaus collection at viewers’ fingertips. But an upcoming special exhibition, presented on the occasion of the centennial of the formation of the Bauhaus, will give visitors a firsthand look at some of the very best from these holdings.

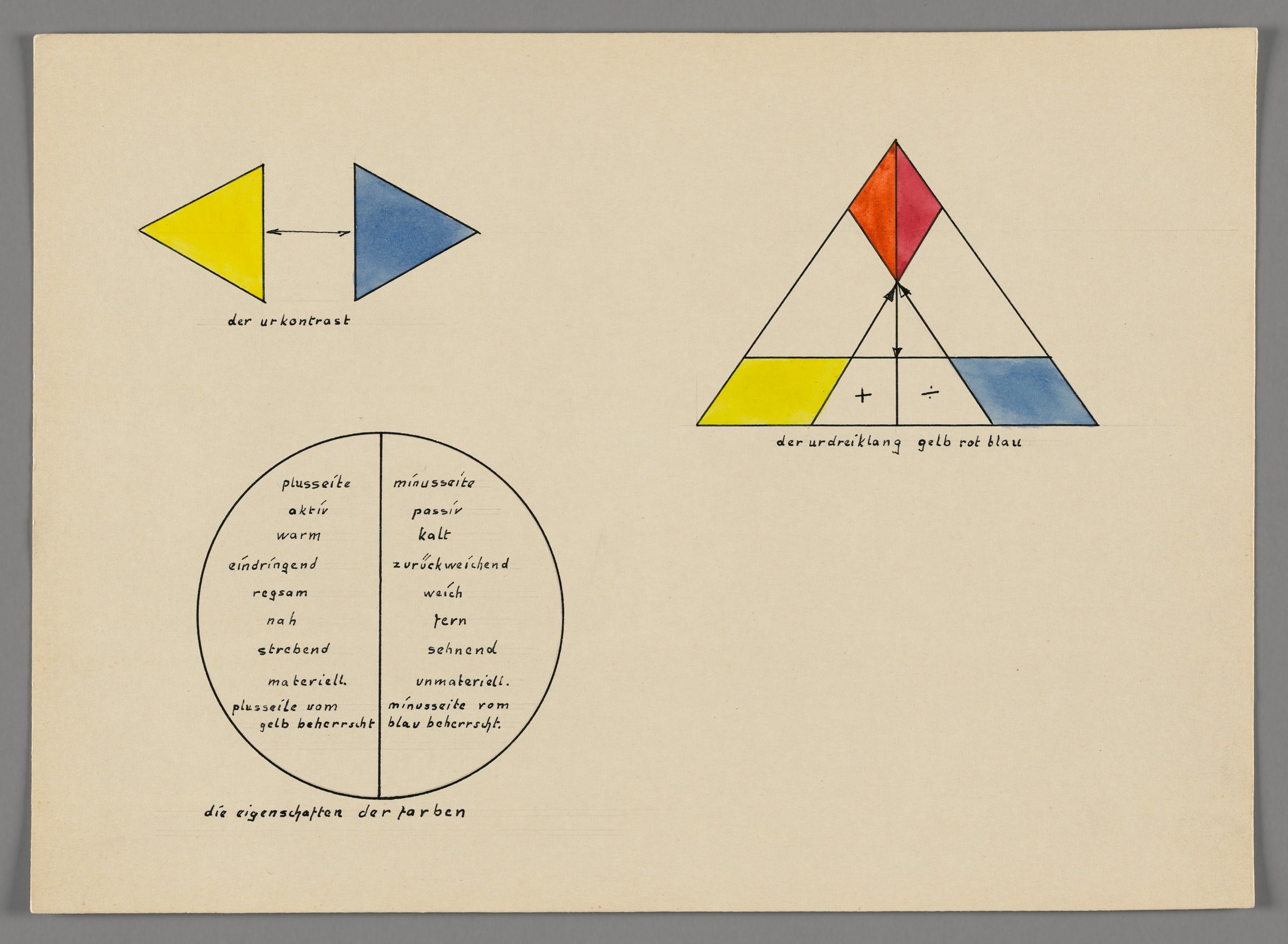

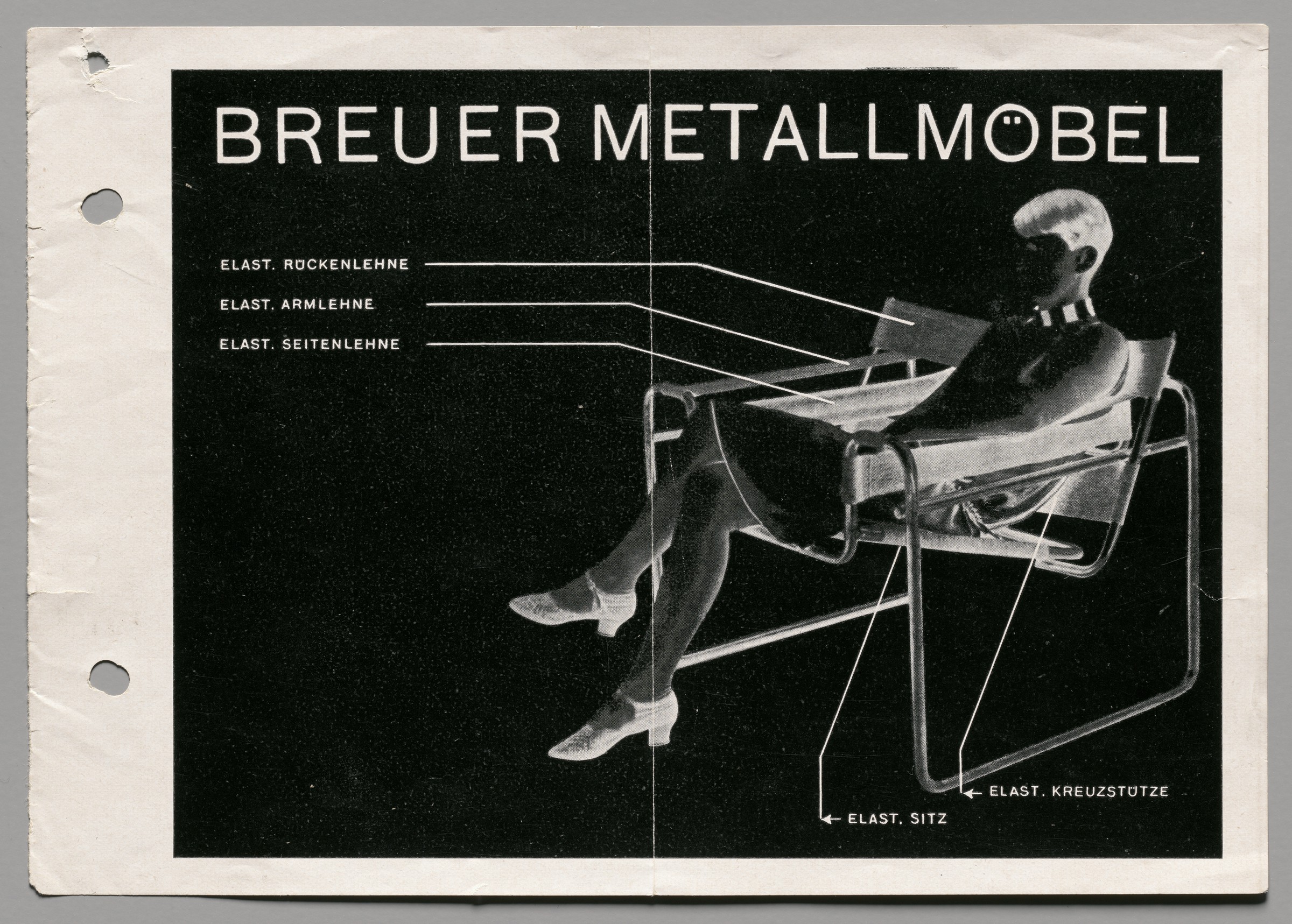

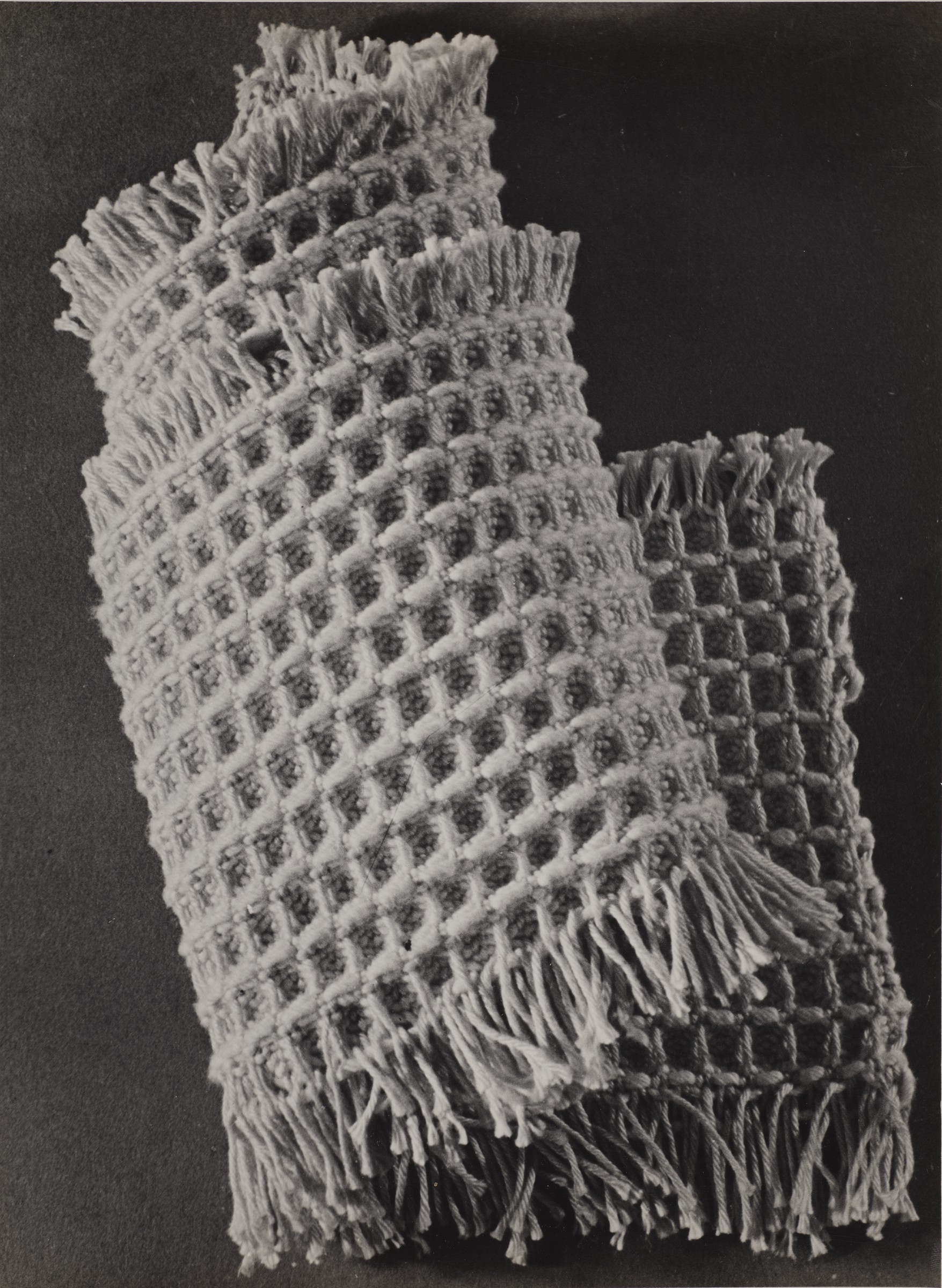

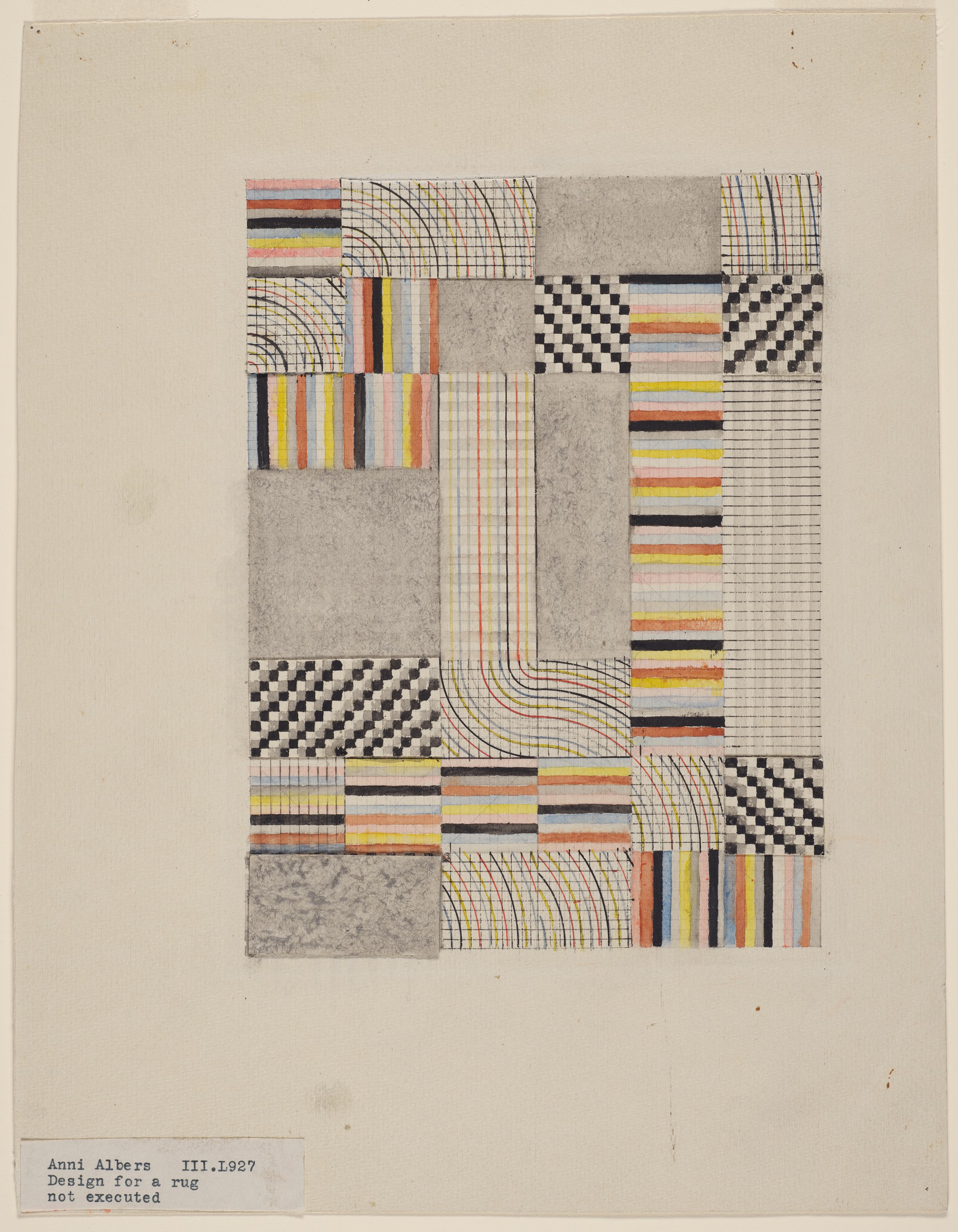

The Bauhaus and Harvard, on view February 8 through July 28, 2019, will feature approximately 200 works, including textiles, paintings, photographs, furniture, and archival materials, drawn almost entirely from the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s rich collection.

Laura Muir, research curator for academic and public programs and former assistant curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, has spent the past several years organizing the exhibition as well as a full slate of related programming. We sat down with her to learn more about the exhibition and the enduring appeal of the Bauhaus.

Index: What are some of the goals of the exhibition?

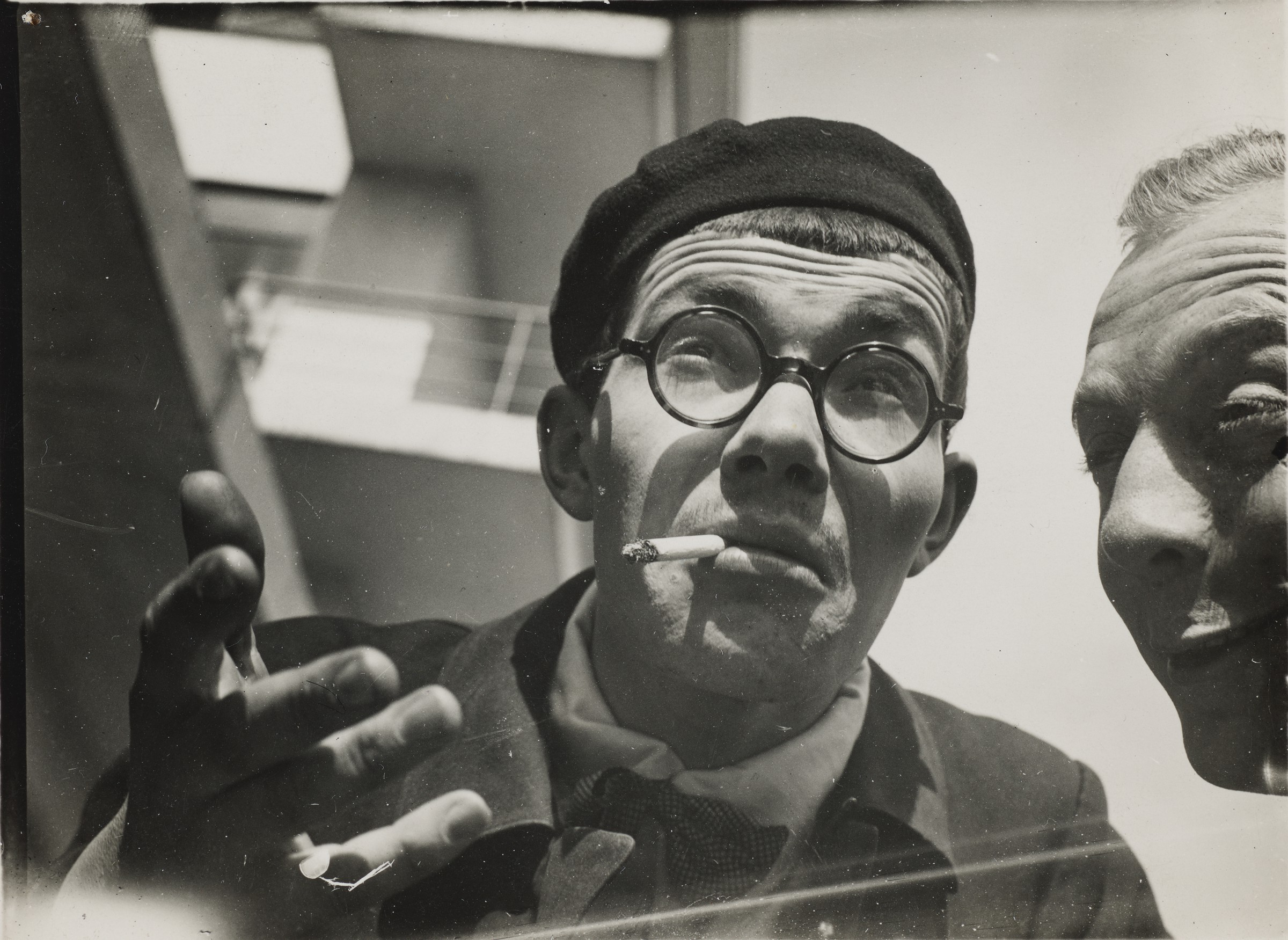

Laura Muir: The Bauhaus centennial gives us the opportunity to reflect on the unique character of this collection and the circumstances that led to its formation in the late 1940s with the help of Walter Gropius. Gropius, director of the Bauhaus from its founding in 1919 until 1928, remained in close contact with many of his former colleagues long after the school closed in 1933 under pressure from Germany’s Nazi government. In 1937, Gropius came to Harvard to join the Department of Architecture. After World War II, Charles Kuhn, curator of Harvard’s Germanic Museum (today’s Busch-Reisinger Museum), worked with Gropius to contact former Bauhaus affiliates to establish a Bauhaus archive—the seeds of today’s collection.

In the exhibition, we want to recognize Gropius’s essential role in establishing the Bauhaus collection, but also underscore the fact that it was very much a group effort. The collection could not have come into being without the participation of many other former members of the Bauhaus community who felt tremendously invested in this initiative and generously donated works of art, design objects, and archival materials.