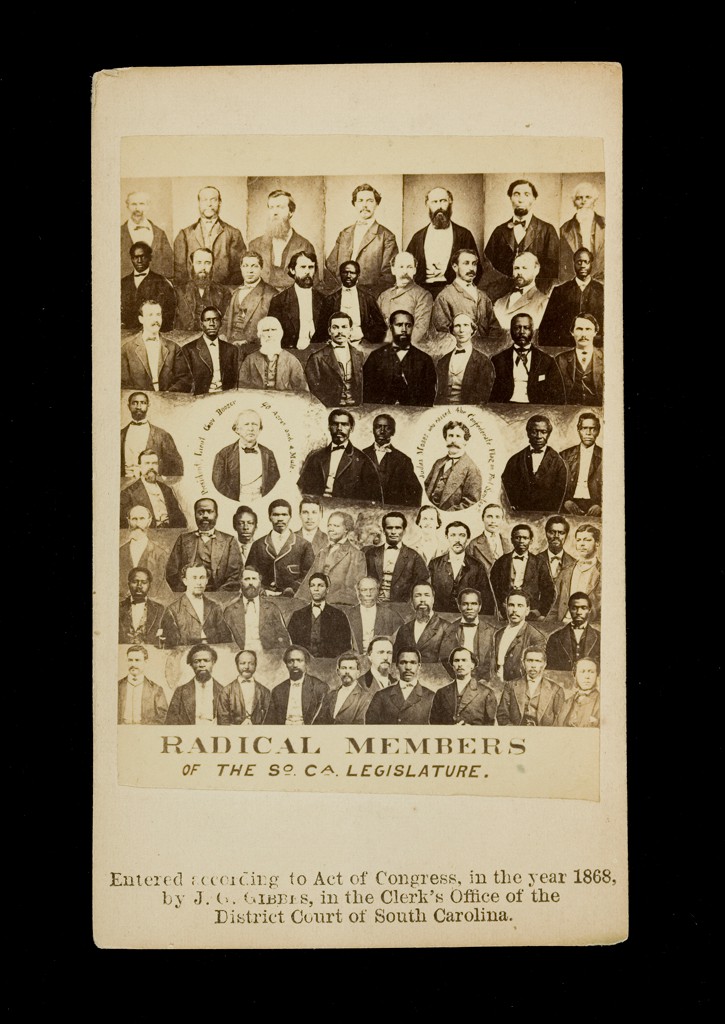

On June 19, 1865, Union troops marched into Texas, the westernmost Confederate state, bringing news to enslaved African Americans that they were free. Four years later, in 1869, the Fifteenth Amendment passed.

The amendment decreed that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Despite the law’s clear mandate, the next 100 years were marked by both systematic attempts to suppress the voting rights of Black Americans and courageous efforts to fight discriminatory barriers to the ballot box.

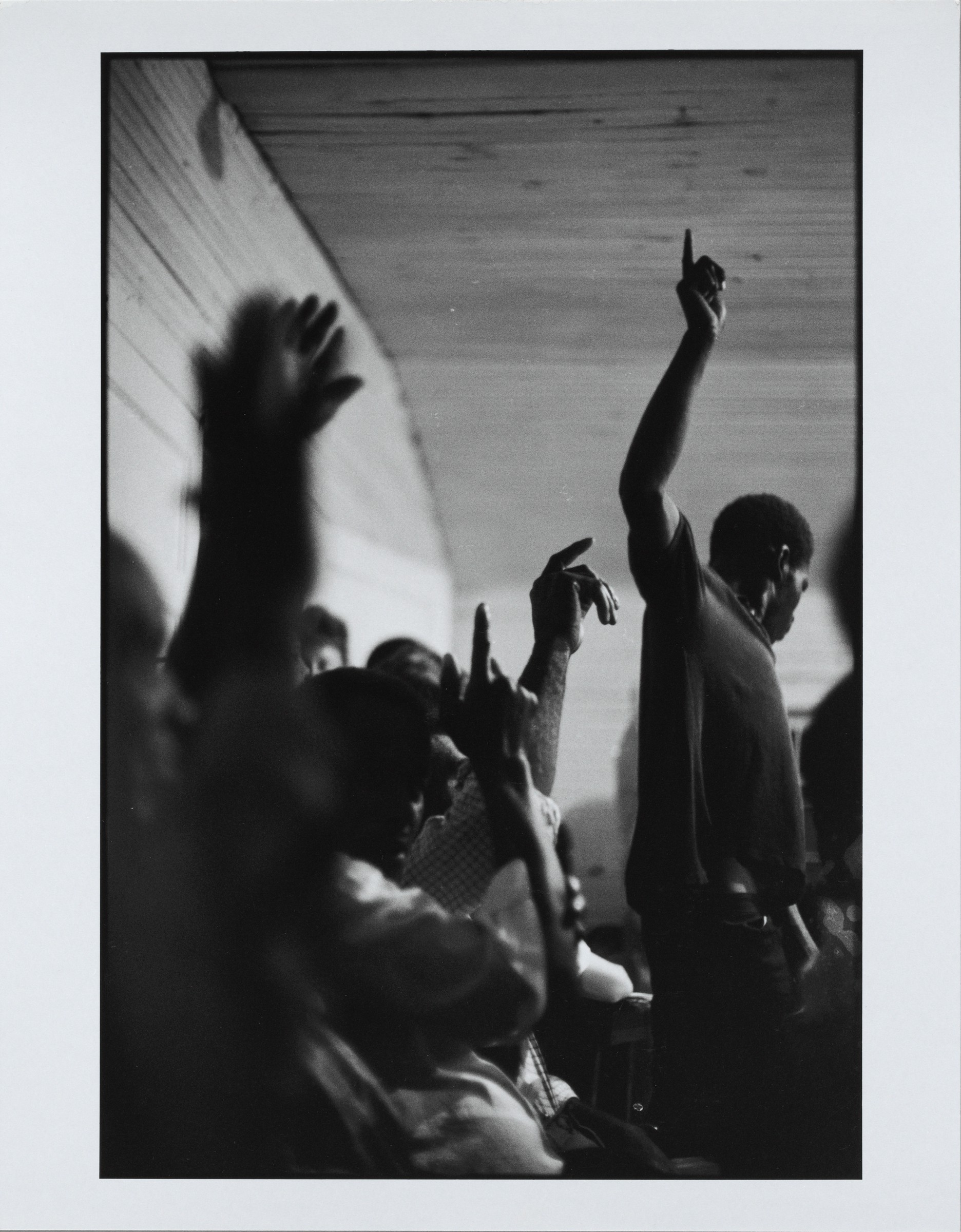

This article, the second in a series of three written in honor of Juneteenth, features works selected as documents of and commentaries on the struggle for full and equal voting rights, from Emancipation to the Civil Rights Movement. These works vividly communicate the profound power of enfranchisement and the dramatic change that can emerge when all citizens have a voice in politics.

Though voting rights have expanded significantly since Emancipation through the work and sacrifice of countless activists, American democracy remains imperfect, and voter suppression, especially targeting people of color, remains a pronounced feature of contemporary politics. With the 2020 elections fast approaching, these works are urgent reminders of the long and unfinished history to fulfill the promise of the Fifteenth Amendment.