The 13th-century Japanese sculpture Prince Shōtoku at Age Two has long captivated curators, conservators, and visitors alike. First acquired by American Ellery Sedgwick in 1936, the sculpture is now a promised gift to the Harvard Art Museums from Walter C. Sedgwick, his grandson.

“It’s an incredibly compelling and charismatic object,” said Rachel Saunders, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Associate Curator of Asian Art. Saunders is curating an upcoming exhibition on the sculpture and related objects, titled Prince Shōtoku: The Secrets Within (May 25–August 11, 2019). “Prince Shōtoku has a way of drawing people to him, and in so doing he has inspired much research and investigation into his origins.”

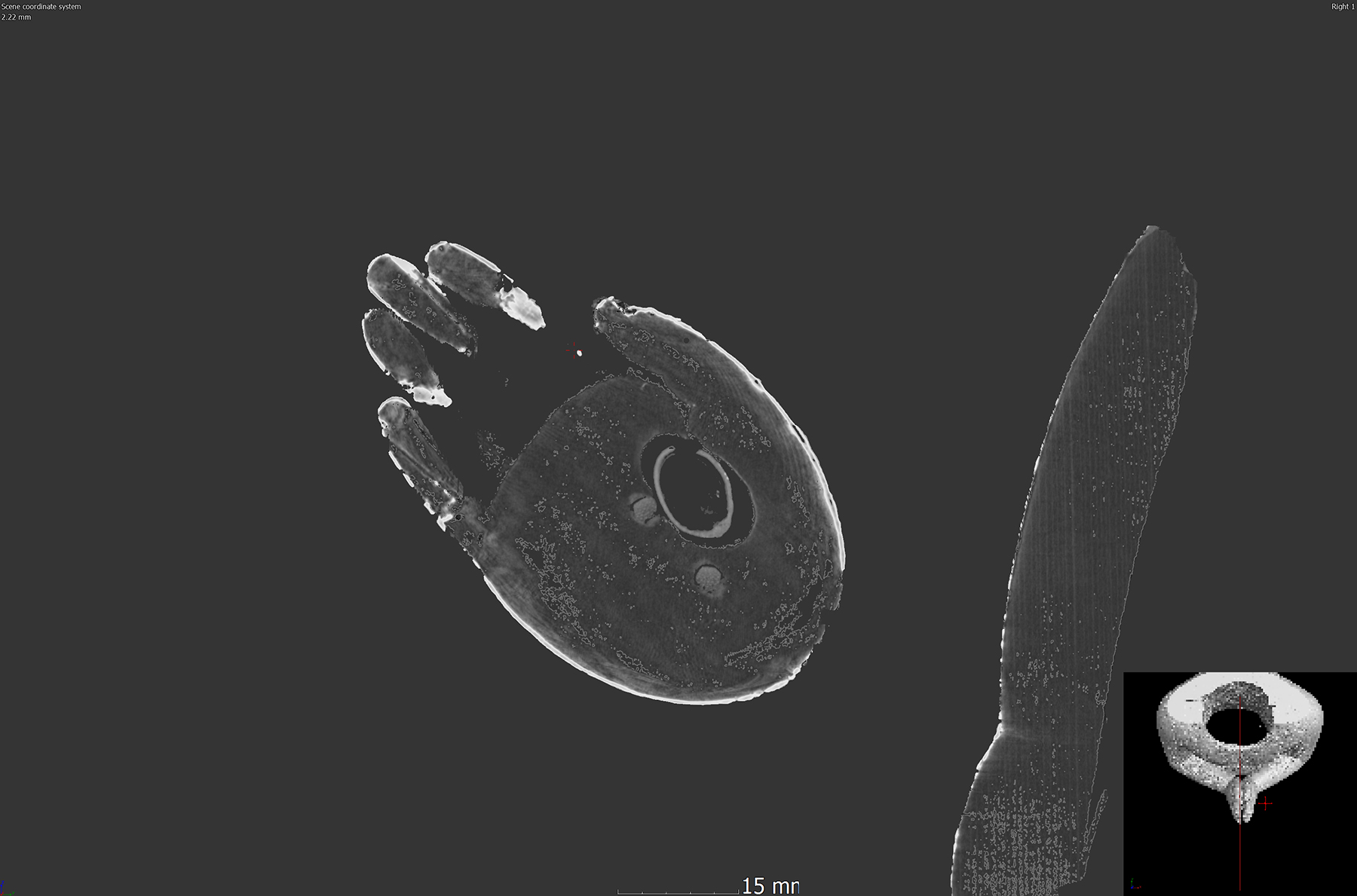

Made of hollowed wood, the sculpture portrays Shōtoku Taishi (c. 574–622), the so-called father of Buddhism in Japan. He is depicted as a two year old (one year old by Western count), in the moment after he is said to have stood up, taken several steps forward, placed his hands together, and chanted the name of the Buddha, manifesting a relic between his hands. After his death, Shōtoku was venerated as a religious and cultural hero, and represented at various ages in both painting and sculpture. The statue acquired by Sedgwick is the earliest datable example of a sculpture of the prince at age two, and is regarded as the most elegantly crafted of its type and time.