It all started with six Chinese silk handkerchiefs.

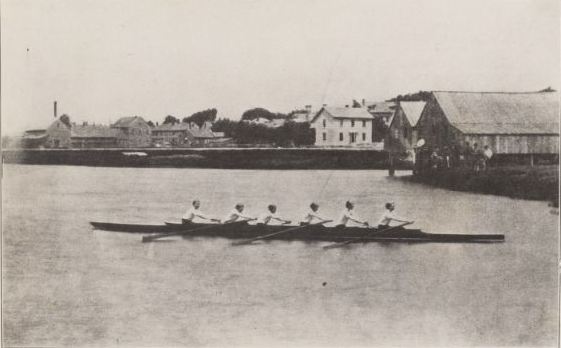

According to the Harvard Crimson, on June 19, 1858, Harvard crew members Charles Eliot (Class of 1853) and Benjamin Crowninshield (Class of 1858) bought six red handkerchiefs just before a regatta to distinguish their team from its competitors. As team members wiped the sweat from their brows during the race, the handkerchiefs turned from red to a deep crimson. News of the colored scarves spread, and the signature Harvard color was born.

Or was it? In the 1860s, magenta became all the fashion throughout the United States, and as the trend hit Harvard’s campus, the color was soon vying with the original crimson. In 1864 a Harvard crew member bought magenta scarves for his teammates. Even the first issue of the publication we know as the Harvard Crimson was called theMagenta (Harvard Crimson 2004).

The legend goes that the tipping point between the two colors came at an 1875 regatta race with Union College of Schenectady, when both teams claimed magenta as their color. This crisis prompted a meeting in Holden Chapel on May 6, 1875, with Harvard faculty, students, and alumni in attendance. At the meeting an alumnus admitted that the only reason he bought those magenta scarves in 1864 was because the shop was out of crimson ones. A vote was taken and crimson won by a large majority (Harvard Crimson 2004). The student newspaper renamed itself the Crimson, stating that “The magenta is not now, and, as was shown in the meeting, never has been, the right color of Harvard” (The Crimson 1875).

Union College Magazine, however, has a slightly different story. According to them, there was no dispute at the 1875 race at all. Apparently, a Union College student had written to Harvard before the regatta claiming that magenta belonged to them and that he wanted to avoid confusion at the upcoming race. News of the letter made its way around Harvard, the alumnus made his confession, and the university returned to crimson (Union College Magazine 2004).

In 1909, Charles Eliot, who had first bought the crimson handkerchiefs for his team, had just stepped down as president of the college. The new president, A. Lawrence Lowell, knowing that the college was running out of crimson materials, tried looking for a local dye source that could get the exact right “arterial red,” in Lowell’s words. He eventually worked with Lewando’s French Dye House, in Watertown, MA, which protected the secret formula for decades (Harvard University Archives 1910).

In 1910 it became official: the Harvard Corporation designated crimson as the official color of the school in honor of Eliot. The corporation’s memorandum notes that a Miss Devens kindly donated one of the original handkerchiefs to the Board of Harvard (Harvard University Archives 1910). A story in the Harvard Graduates’ Magazine notes that, “It was voted that the handkerchief exhibited to the Board be adopted as the standard color of the University, and that it be preserved in the archives of the University” (1910). The now-famous handkerchief continues to rest in the Harvard University Archives, preserving its color for generations to come.

R. Leopoldina Torres is a former Communications Intern (summer 2013) and is pursuing an MLA degree in the Museum Studies Graduate Program at the Harvard Extension School.

“Corporation Records,” Harvard Graduates’ Magazine (September 1910): 84. The Crimson, May 21, 1875, iii. “Going Garnet,” Union College Magazine(Winter 2004). “Memorandum In Regard to the Official Color of Harvard University,” 1910, Harvard University Archives, UAI 20.910.1. Warmflash, Gillian L. “Harvard Explained,” Harvard Crimson, April 11, 2002.