John Singer Sargent was acclaimed for his skill as a portraitist of American high society in the Gilded Age. The Harvard Art Museums hold a famous example of his work: The Breakfast Table, an atmospheric painting featuring his younger sister, Violet.

Few may be aware that our collections also include some of Sargent’s tools and materials—possibly even the very ones used to make the Breakfast Table.

A recent article by Georgina Rayner, associate conservation scientist in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, and Joyce H. Townsend, senior conservation scientist at Tate Britain, highlights this fascinating group of objects. Published in a Sargent-themed edition of Visual Culture in Britain, “Sargent’s Painting Materials: New Discoveries and Their Implications” is the result of Rayner and Townsend’s close technical studies of Sargent’s many painting palettes in collections in both the United Kingdom and the United States, including one at Harvard. Townsend and Rayner first presented their work during the April 2016 conference Sargentology: New Perspectives on the Works of John Singer Sargent.

“Being able to look at an artist’s materials gives you deep insight into that artist’s practice and the choices he made,” said Rayner. She and Townsend investigated and compared such factors as “palette shape and weight, size and shapes of brushes, suppliers of paint, and even how Sargent mixed the paint,” Rayner said.

The palettes are held in institutions small and large, private and public. Townsend researched and wrote about examples from the United Kingdom, held at Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and in a private collection. Rayner handled the U.S. examples: at the Harvard Art Museums; the Sargent House Museum in Gloucester, Massachusetts; the Signet Society in Cambridge, Massachusetts; and the Tavern Club in Boston.

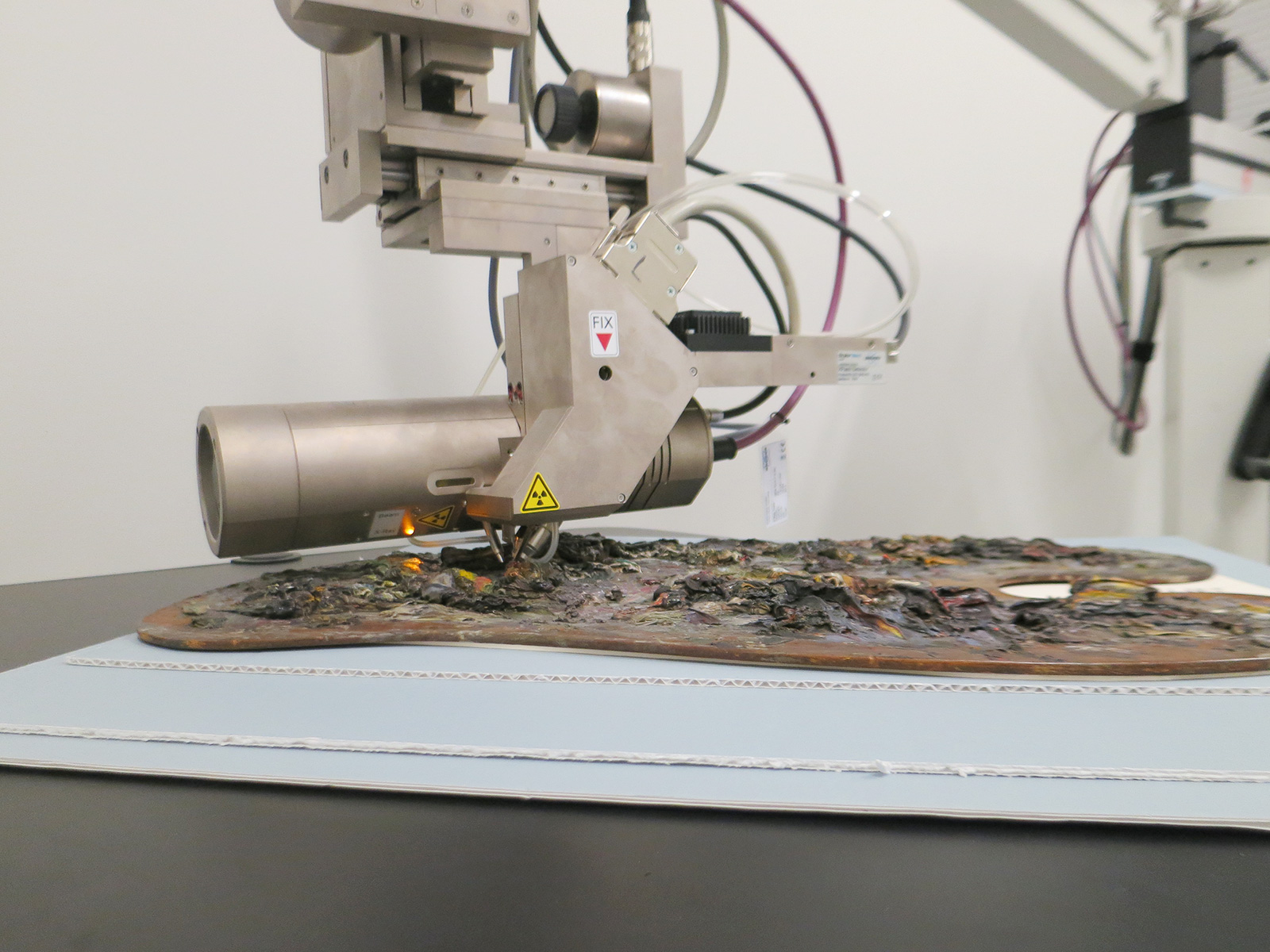

The Harvard example is a kidney-shaped palette, which was found in Sargent’s London studio after his death in 1925. It was given to the Fogg Museum by Sargent’s sisters, Emily and Violet. They also donated a number of other painting materials from Sargent’s studio on Columbus Avenue in Boston, such as paintbrushes and a paint box containing numerous tubes of paint.