When pioneering American conceptual artist Sol LeWitt first planned his wall drawings, he envisioned that they would need to be re-executed over time. Years after initial installation, fresh executions of his colorful wall drawings continue, overseen by the artist’s estate following his meticulous specifications.

LeWitt sought to revolutionize the very definition of art with his notion that “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” Because his wall drawings lack traditional supports like canvas or paper, the instructions for each of them were created as art forms in and of themselves—thus allowing for multiple installations, with no single execution dubbed “original.” As a result, conservation or restoration of these works does not apply in the traditional sense; a drawing may simply be removed and reinstalled when needs arise.

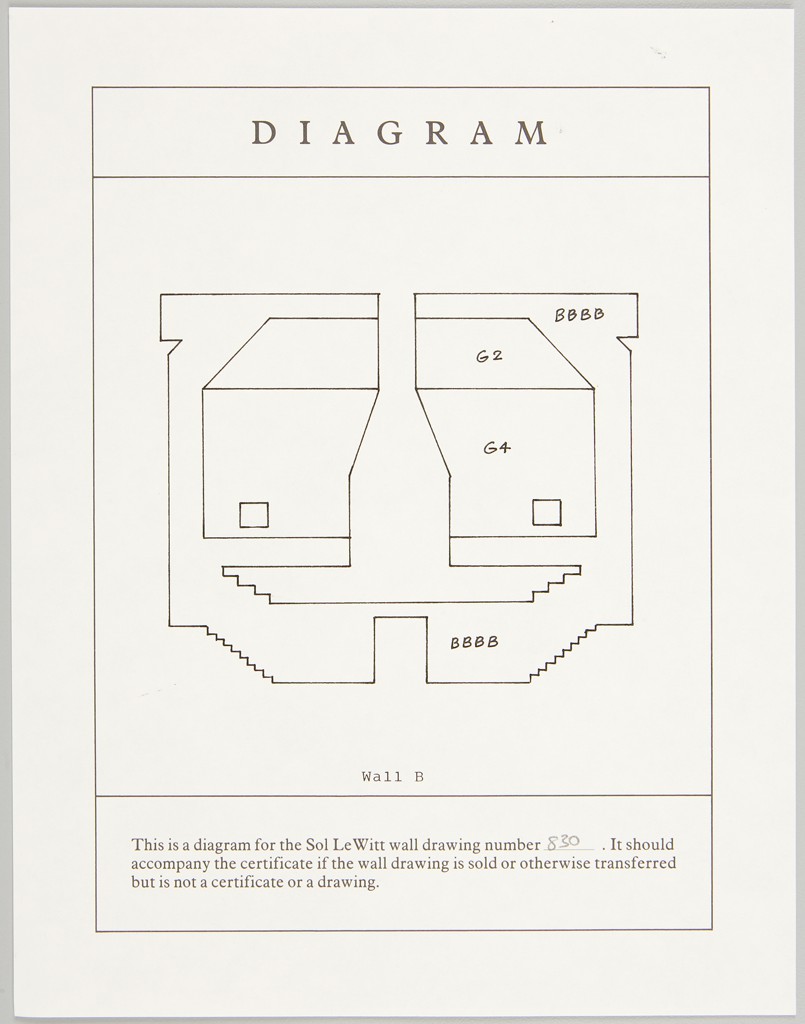

One such example was recently rendered for a second time in the lobby of Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler Building while the space underwent significant renovation. Two draftspeople from the Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing Study Center, based at Yale University, partnered with three artists hired by the Harvard Art Museums to complete the work. Originally executed in 1997, the red, yellow, and blue Wall Drawing #830 (Four Isometric Figures with Color Ink Washes Superimposed) was faded and in need of attention.