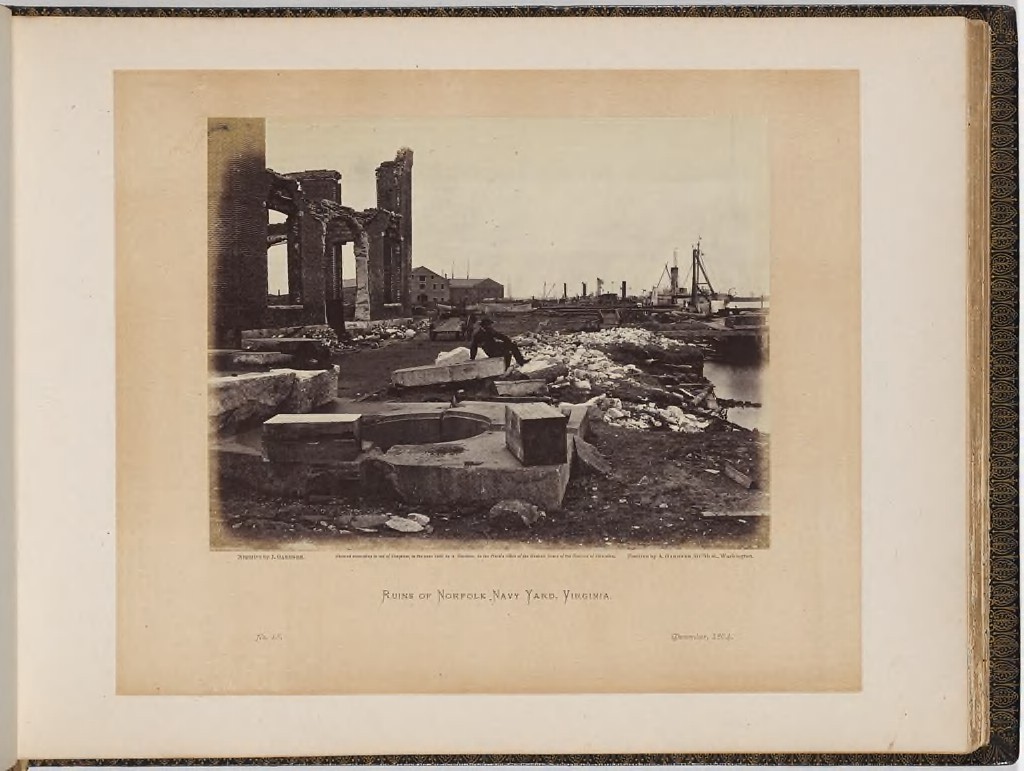

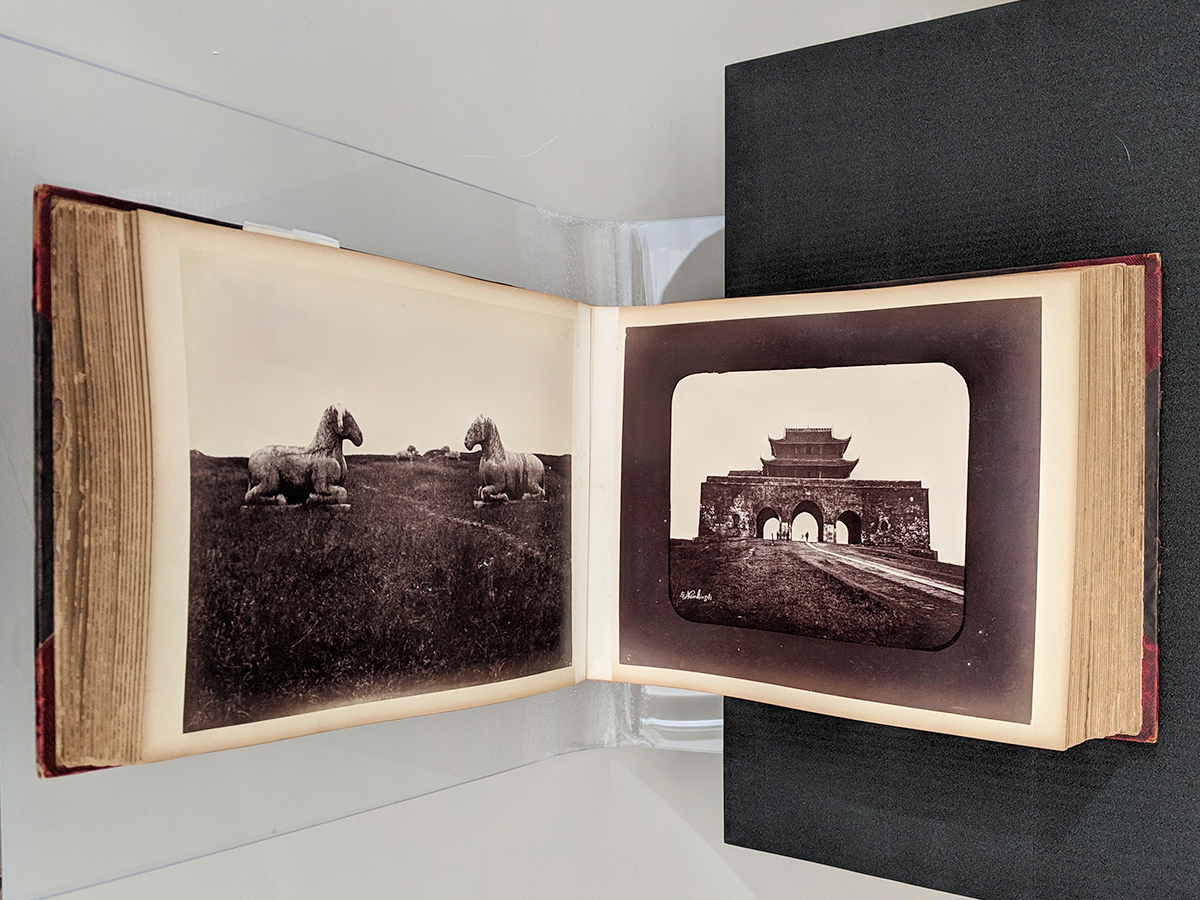

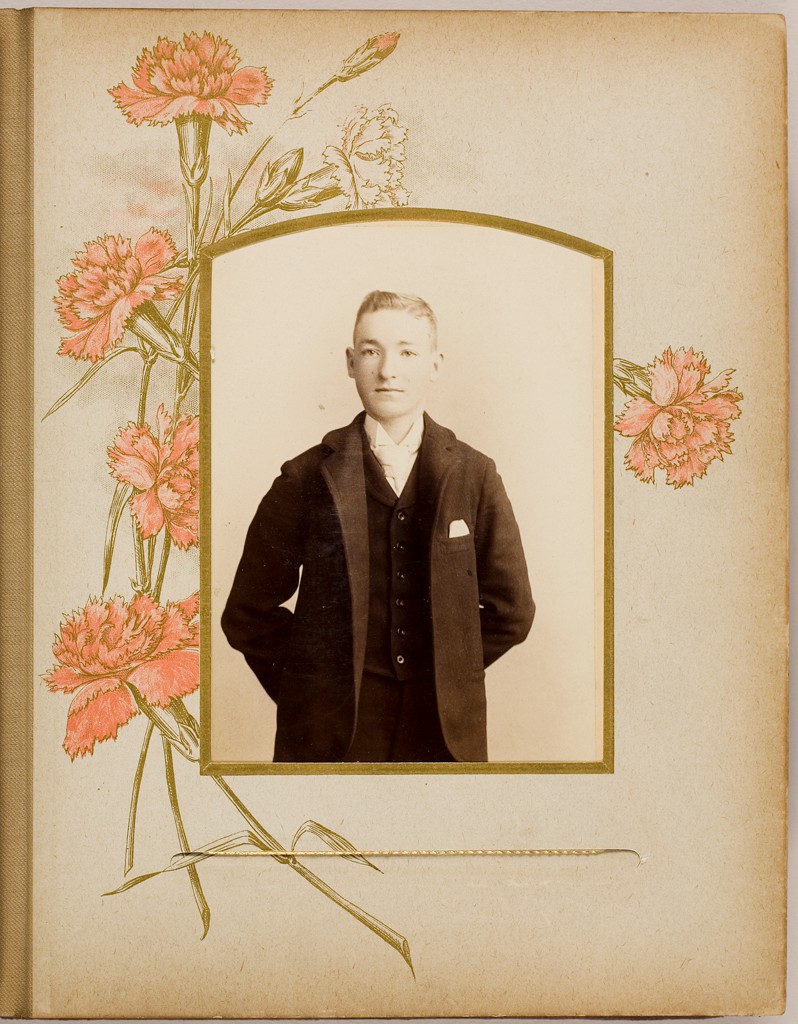

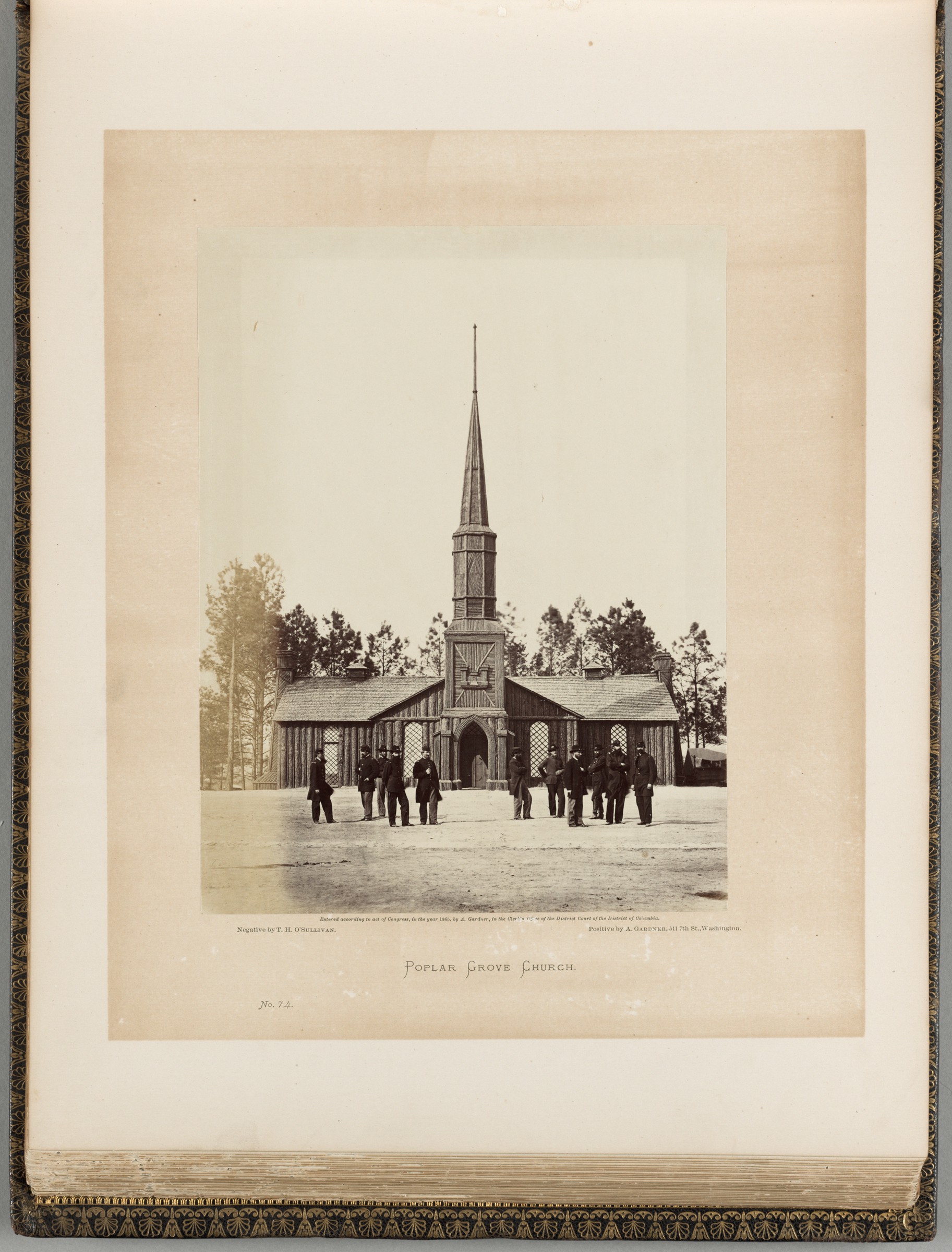

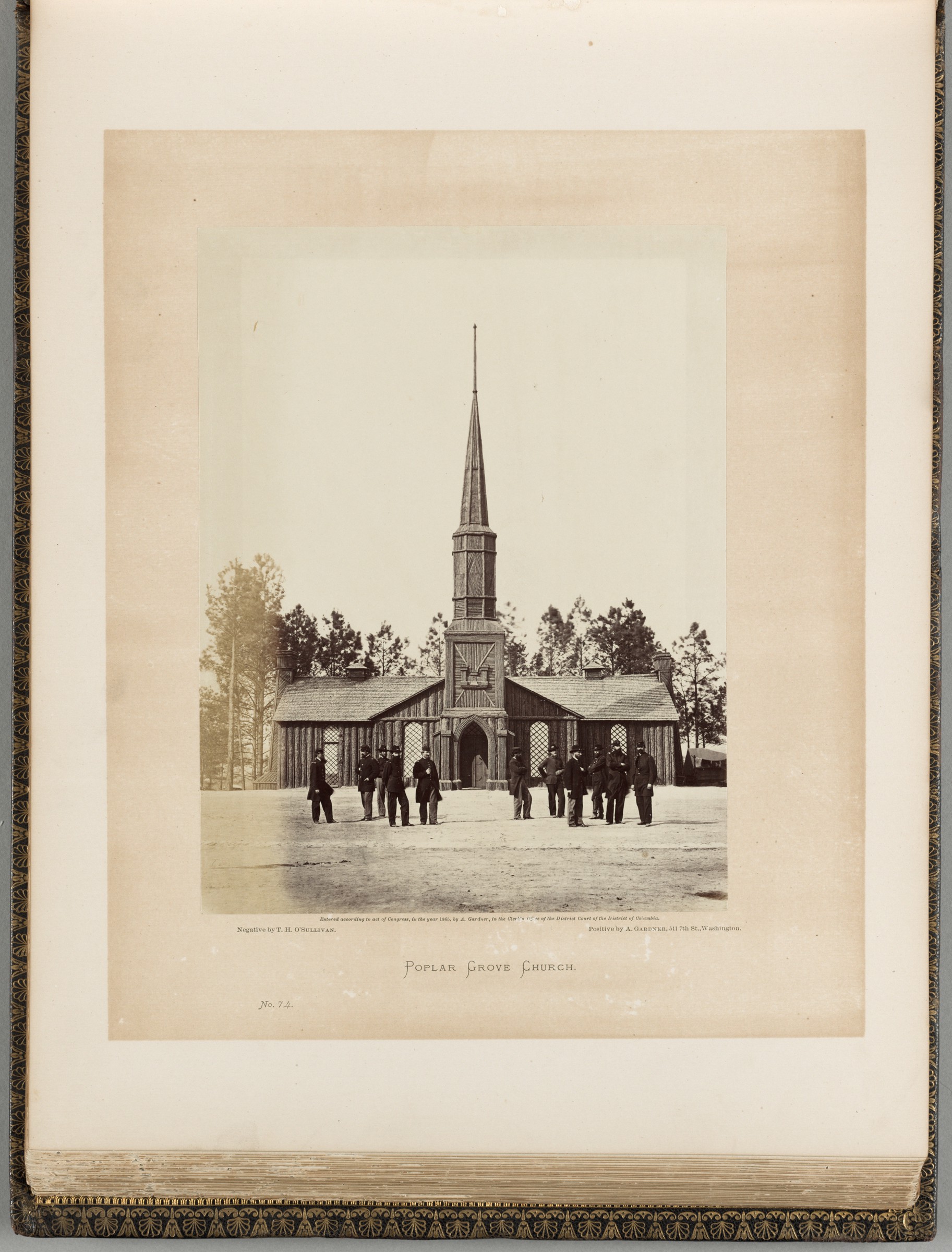

Before the existence of printing technologies that could rapidly reproduce photographs in ink, books in the 19th century were illustrated with actual photographs. As we consider not only these photobooks but also the scrapbooks and albums in our collections, we ask: how does the context in which we view photographs influence the meaning we derive from them?

The Harvard Art Museums have more than 100 photographically illustrated books, albums, and scrapbooks in the collections; these works cover a wide range of subjects, including anatomy, travel, ethnography, documentary photography, architectural history, and art history.

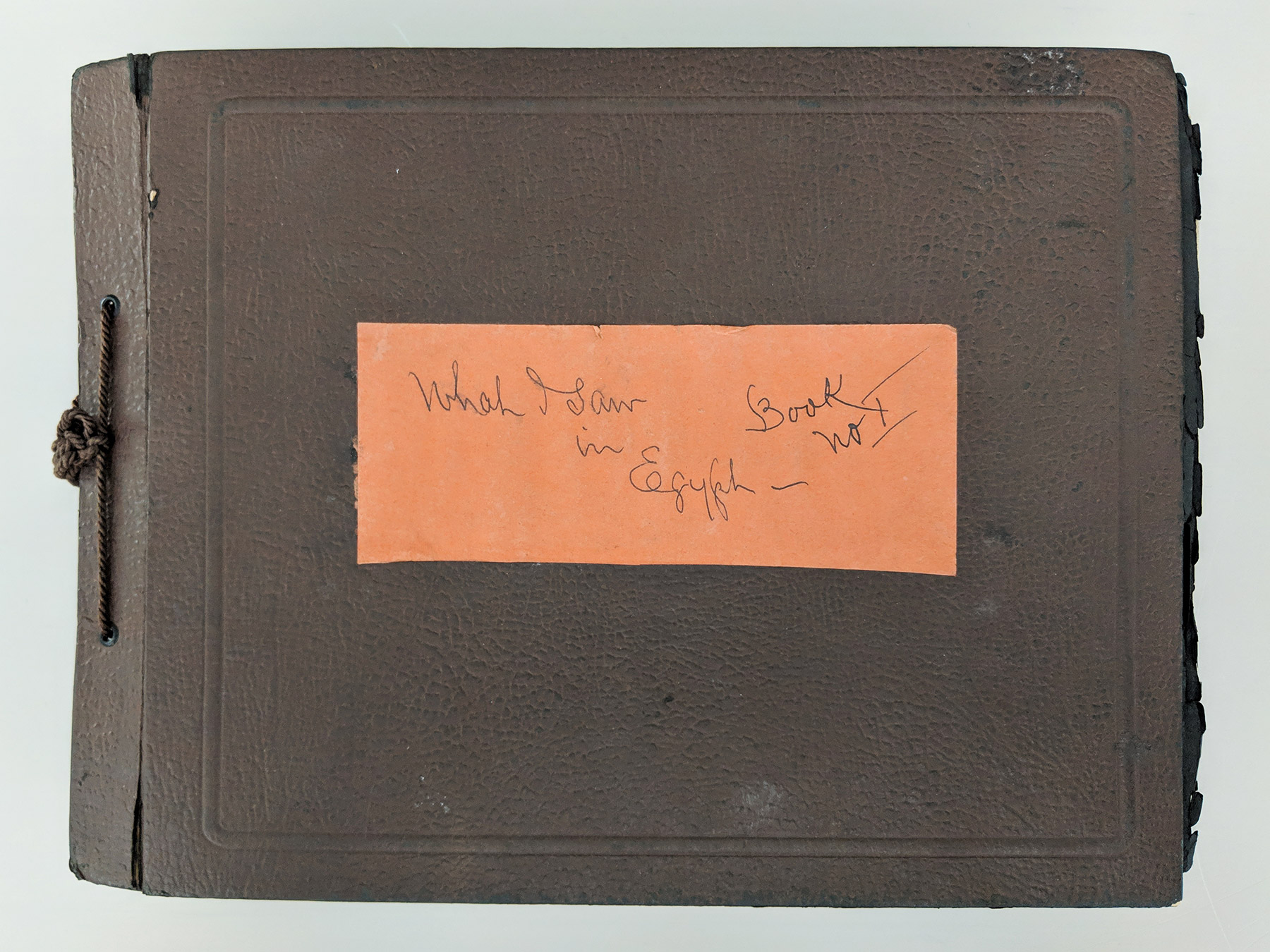

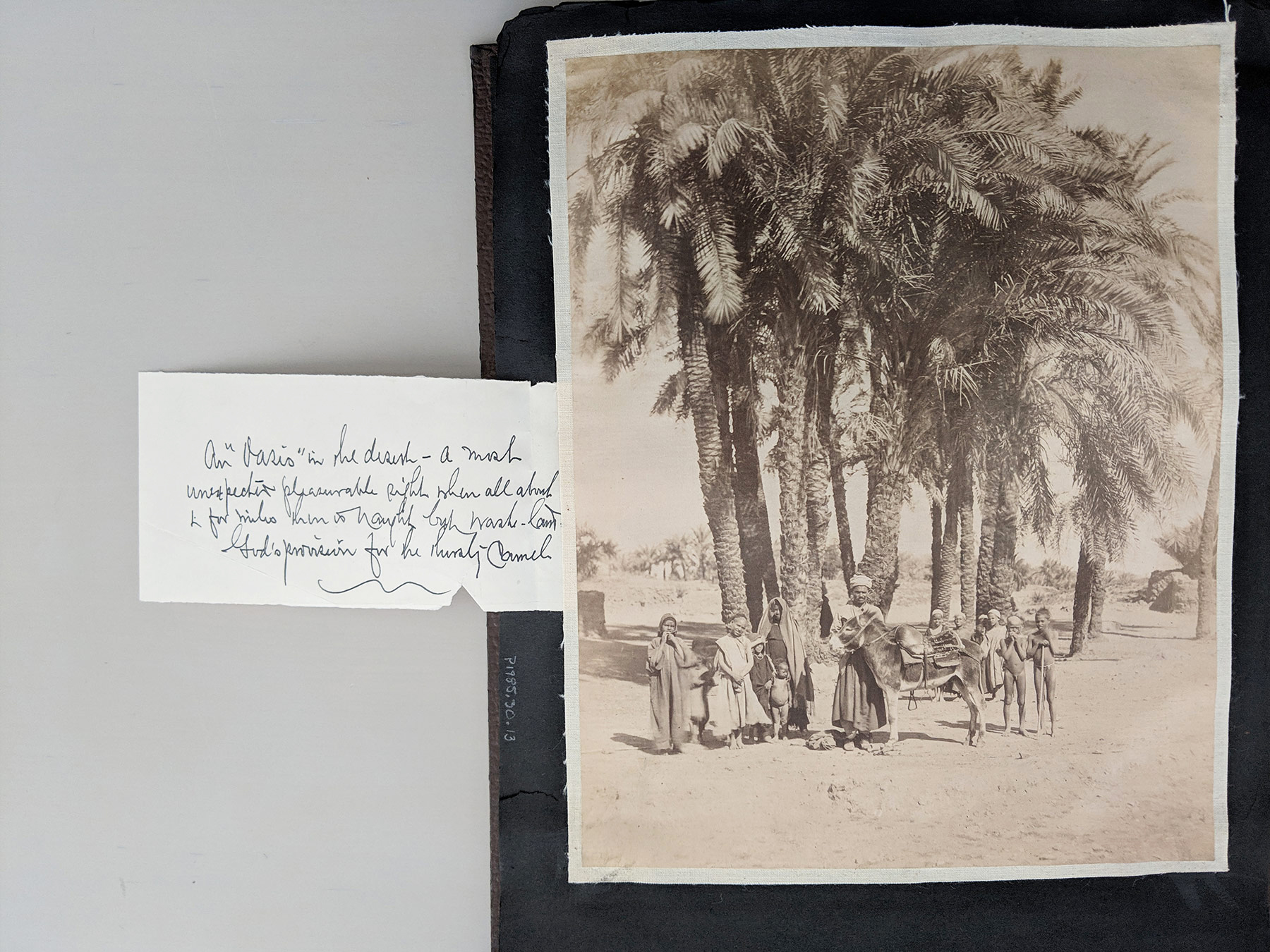

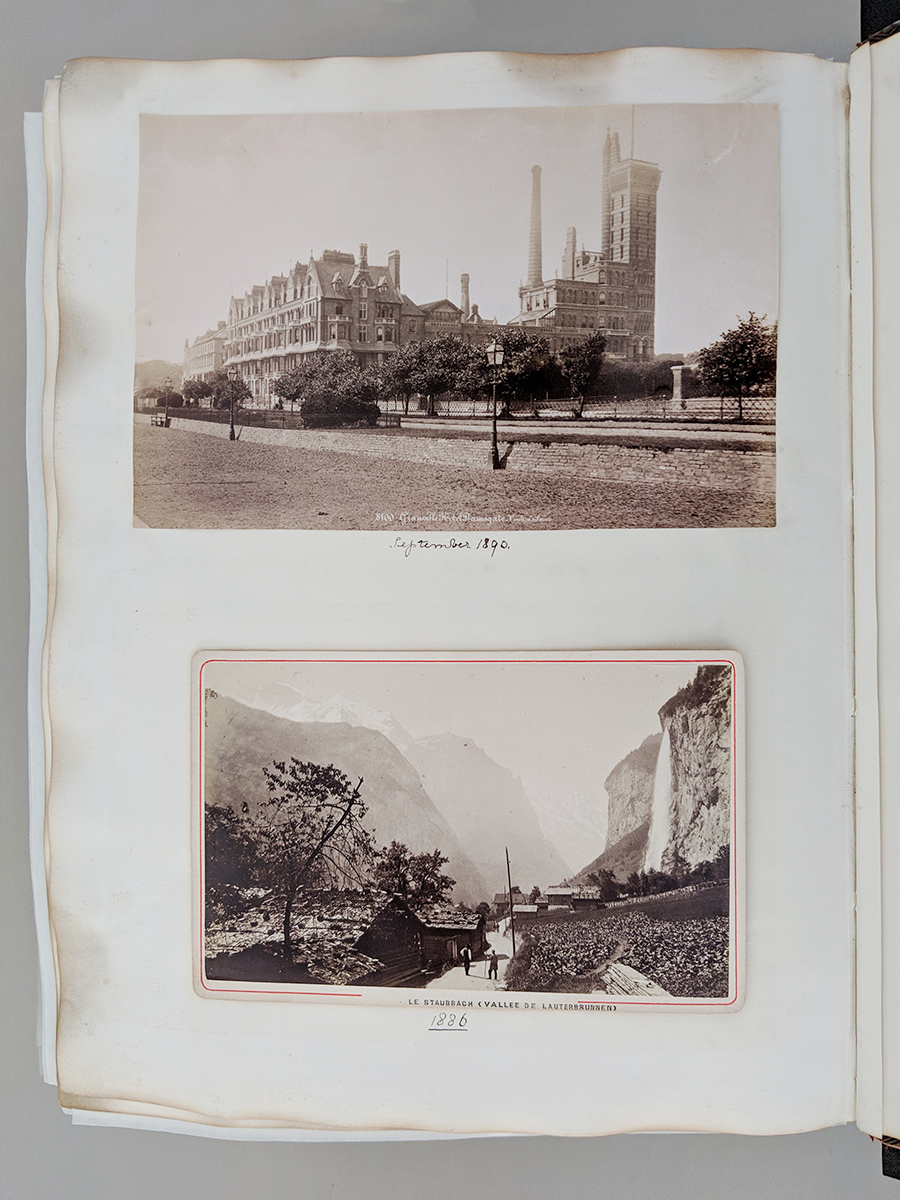

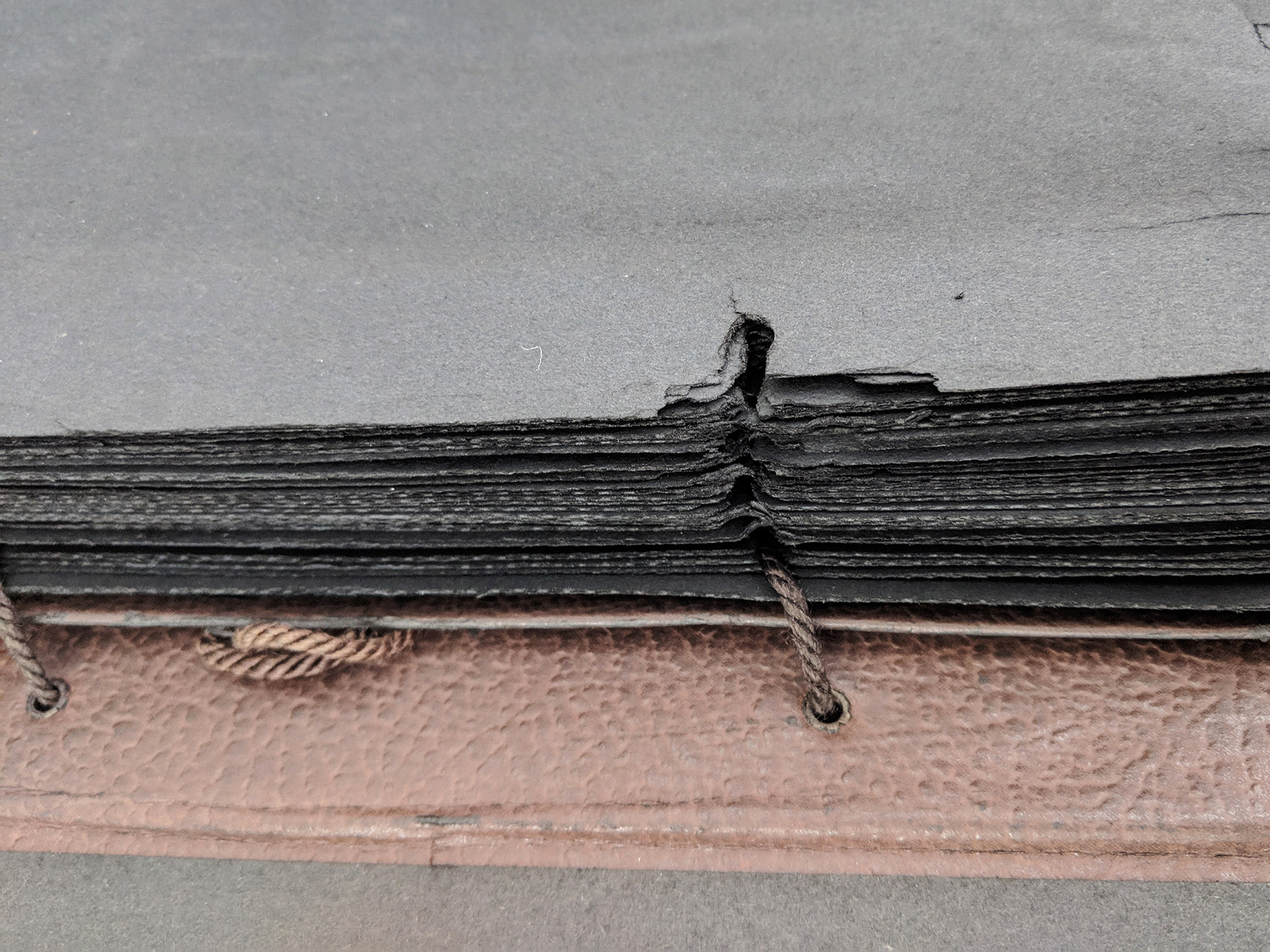

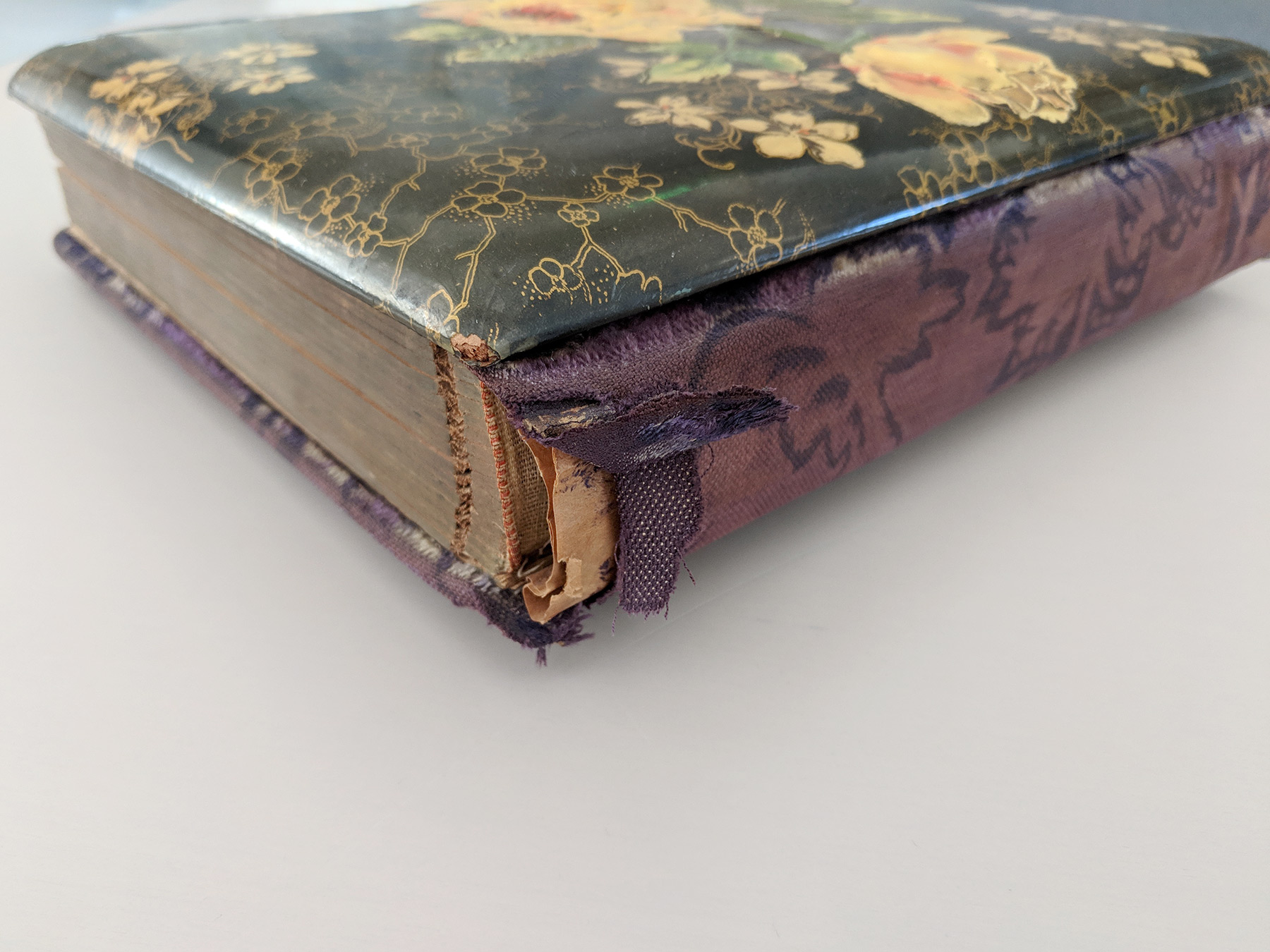

The terminology used to describe books that contain photographs can be confusing, and types often overlap. The term “photographically illustrated book” denotes books in which photographs are used to illustrate text but do not constitute the primary content. An album, on the other hand, is generally used to describe a book in which a single type of image—a photograph, for instance—is displayed consistently and uniformly and is the focus of the book. Scrapbooks are yet another category: they are one-of-a-kind, handmade assemblages of photographs and other printed, handwritten, and handmade materials. All these types provide contextual information that might be lost if the images were to be viewed in isolation. However, bound formats can also pose unique challenges to interpretation and preservation.