It’s been nearly 200 years since the debut of Théodore Géricault’s groundbreaking The Raft of the Medusa at the Paris Salon of 1819. Yet it remains as provocative and inspirational as ever—look no further than a recent music video from Beyoncé and Jay-Z, in which the painting serves as a backdrop for biting cultural commentary.

The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19) depicts a scene from the aftermath of an infamous 19th-century French tragedy in which 150 soldiers and other passengers from the naval frigate Medusa were stranded at sea for nearly two weeks aboard a makeshift raft. Only 10 people survived to tell of the ordeal, which included starvation, drowning, and cannibalism.

Though the painting is on permanent view at the Louvre, its admirers can soon appreciate related works and other Géricault drawings, watercolors, lithographs, and paintings through an exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums. Mutiny: Works by Géricault (September 1, 2018–January 6, 2019) features approximately 40 objects by the Romantic artist, most of which come from the museums’ own holdings.

“We’re lucky to have one of the most comprehensive Géricault collections in the country,” said A. Cassandra Albinson, the Margaret S. Winthrop Curator of European Art, who put together the exhibition. The collection was assembled and given to the museums in the first half of the 20th century in large part by Harvard benefactor Grenville L. Winthrop, and the terms of his bequest stipulate that Winthrop Collection objects cannot travel beyond the museums. The exhibition is rounded out by other generous gifts from donors past and present, including three Boston-area collectors.

A Brief but Influential Career

Born in 1791, Géricault lived only to the age of 32. His artistic practice coincided with Europe’s Restoration period, which lasted from roughly 1814 to 1830, and with France’s efforts to emerge from the tumult of revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. “People were trying to grapple with the aftermath of violence,” Albinson said. “Géricault really dug into questions of what that meant for society.”

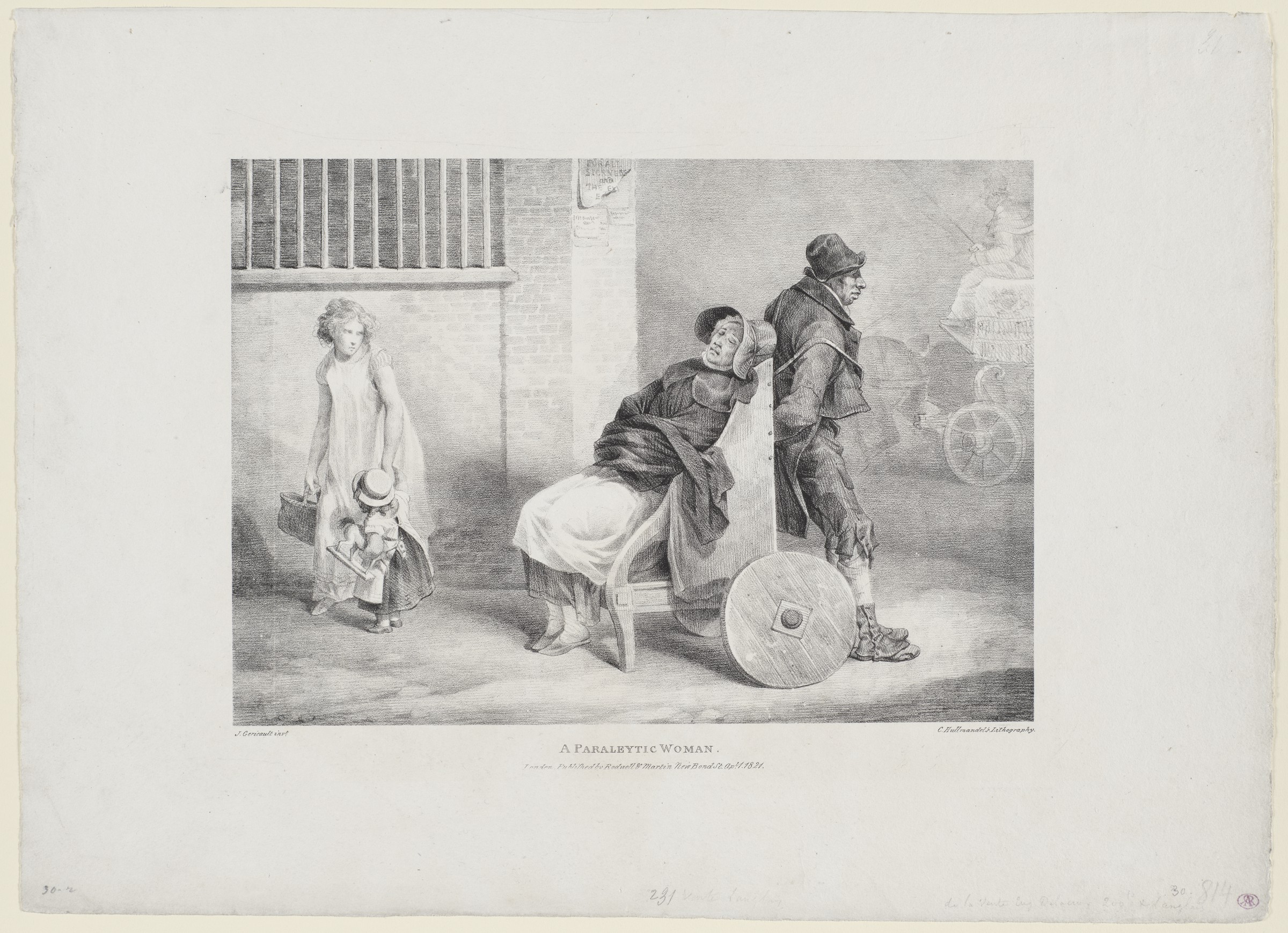

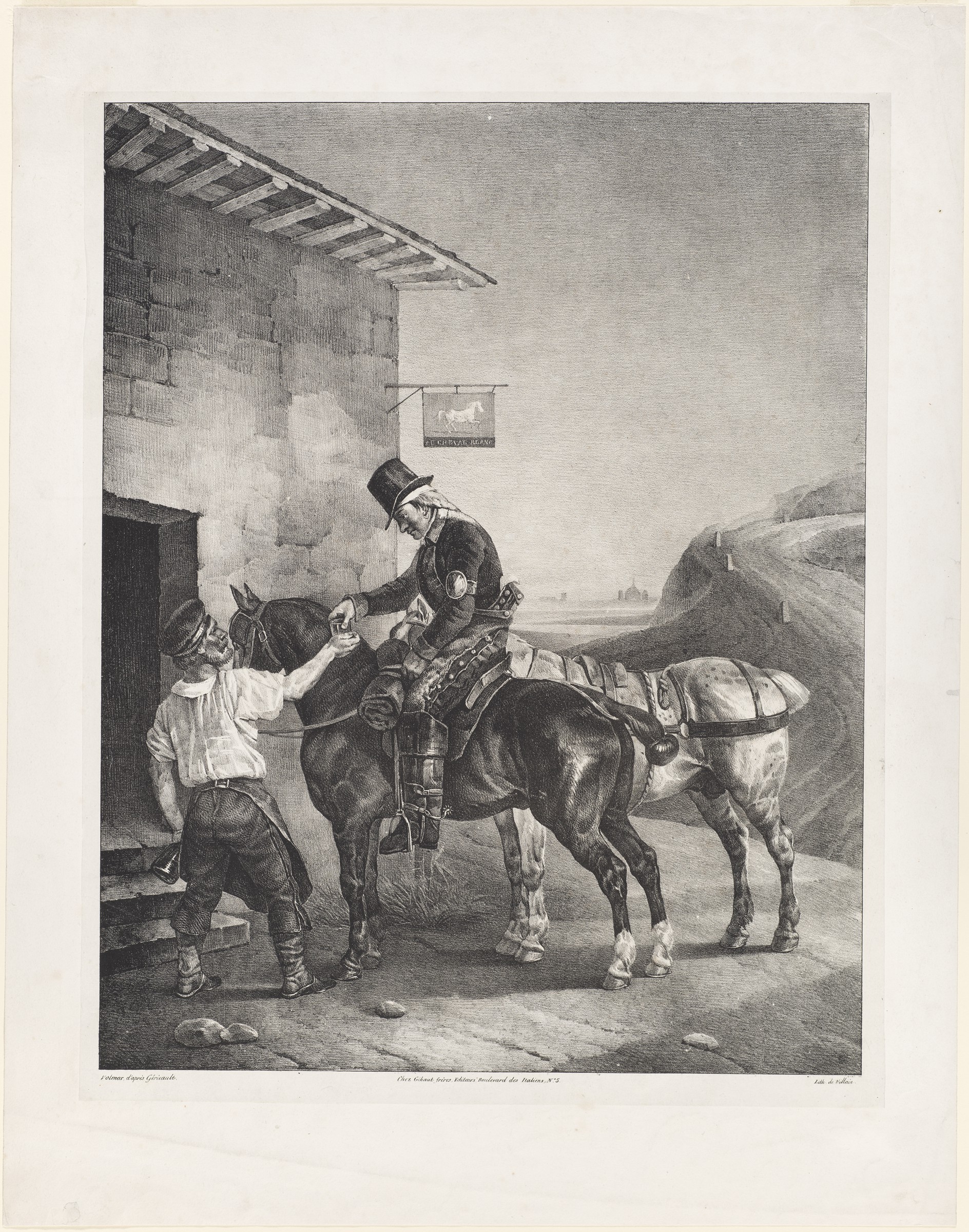

Many of Géricault’s works focus on the everyday, as well as the “casual brutality of modern life,” as Albinson put it. The dispossessed and downtrodden figure prominently—defeated soldiers returning from battle in the 1818 lithograph Return from Russia, for example, or a paralytic woman portrayed in an 1821 work. Géricault also had an interest in depicting domesticated animals, perhaps making an implicit connection between the constraints placed on animals and the mistreatment of the urban poor by society at large.

Organized chronologically in four sections, the exhibition explores these themes in depth. Though Géricault is today famed for his paintings, he also produced masterful watercolors and drawings. In his lifetime, he was most widely known for his prints, and was an early practitioner of lithography. He briefly experimented with “stone paper” prints, which were made using a prepared paper that replicated the properties of the limestone typically used for lithography. One of his surviving stone paper impressions, Lion Devouring a Horse (1821), will be shown in the exhibition, along with the matrix Gericault printed from.