Numbered Jun ware—ceramic vessels marked with a single Chinese numeral on their bases—have long been admired for their blue and purple or magenta glazes and their distinctive shapes. Yet much remains a mystery about these rare objects: how was the clay shaped to form them? And what sort of glaze was used to produce their dazzling, opalescent colors?

The Science of Ceramics

These questions are at the heart of an ongoing investigation of the museums’ collection of 60 numbered Jun ware vessels, conducted for the exhibition Adorning the Inner Court: Jun Ware for the Chinese Palace (May 20–August 13, 2017). The project brought together an interdisciplinary team of curators, conservators, and conservation scientists from the Harvard Art Museums, as well as Kathy King, director of education for Harvard's ceramics program.

Susan Costello, associate conservator of objects and sculpture, and Lucy Cooper, the Beal Family Postdoctoral Fellow in Conservation Science, spearheaded the project with the support of Melissa Moy, the exhibition’s organizer and the Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art. After reviewing the existing literature, they found more questions than answers.

Previous research has focused on traditional Jun ware, which are unnumbered and are characterized by a thick, blue glaze, and unnumbered “splashed” Jun ware, known for their splashes of copper-red pigment that produce purple tones. It is likely that numbered Jun ware has been understudied because examples are so rare. These remarkable objects, believed to have been created in the early 15th century, were used in the private quarters of the Forbidden City, the imperial palace in Beijing. Thus, the project presented a valuable opportunity to contribute new knowledge to the subject.

Mysteries about Manufacturing

Numbered Jun vessels were formed in 14 distinctive shapes and 10 sizes. Given the uniformity within these divisions, it seems likely that the works were made using a mold. But it is also possible that skilled potters made the vessels according to precise specifications outlined by traditional wheel-throwing methods.

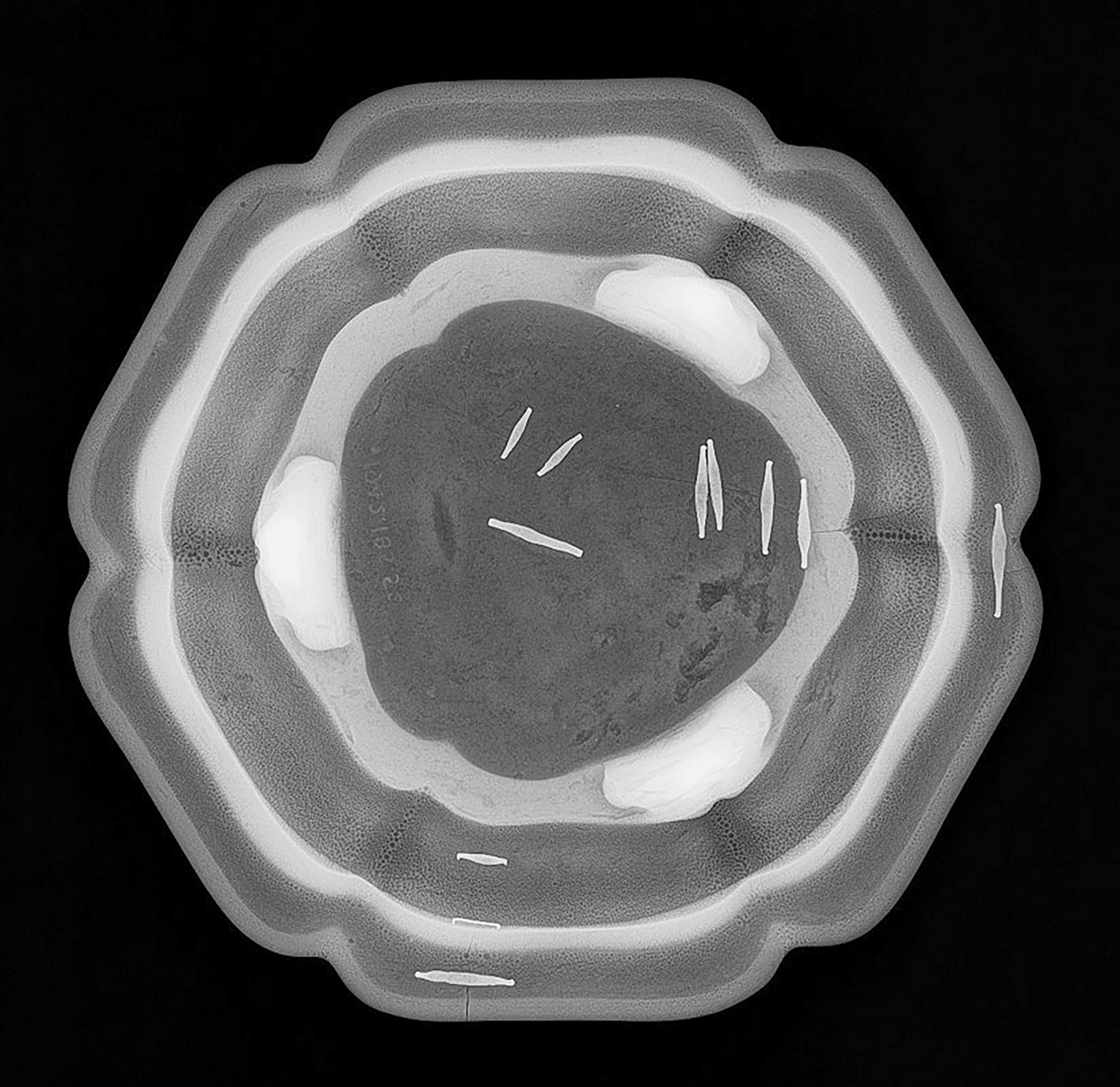

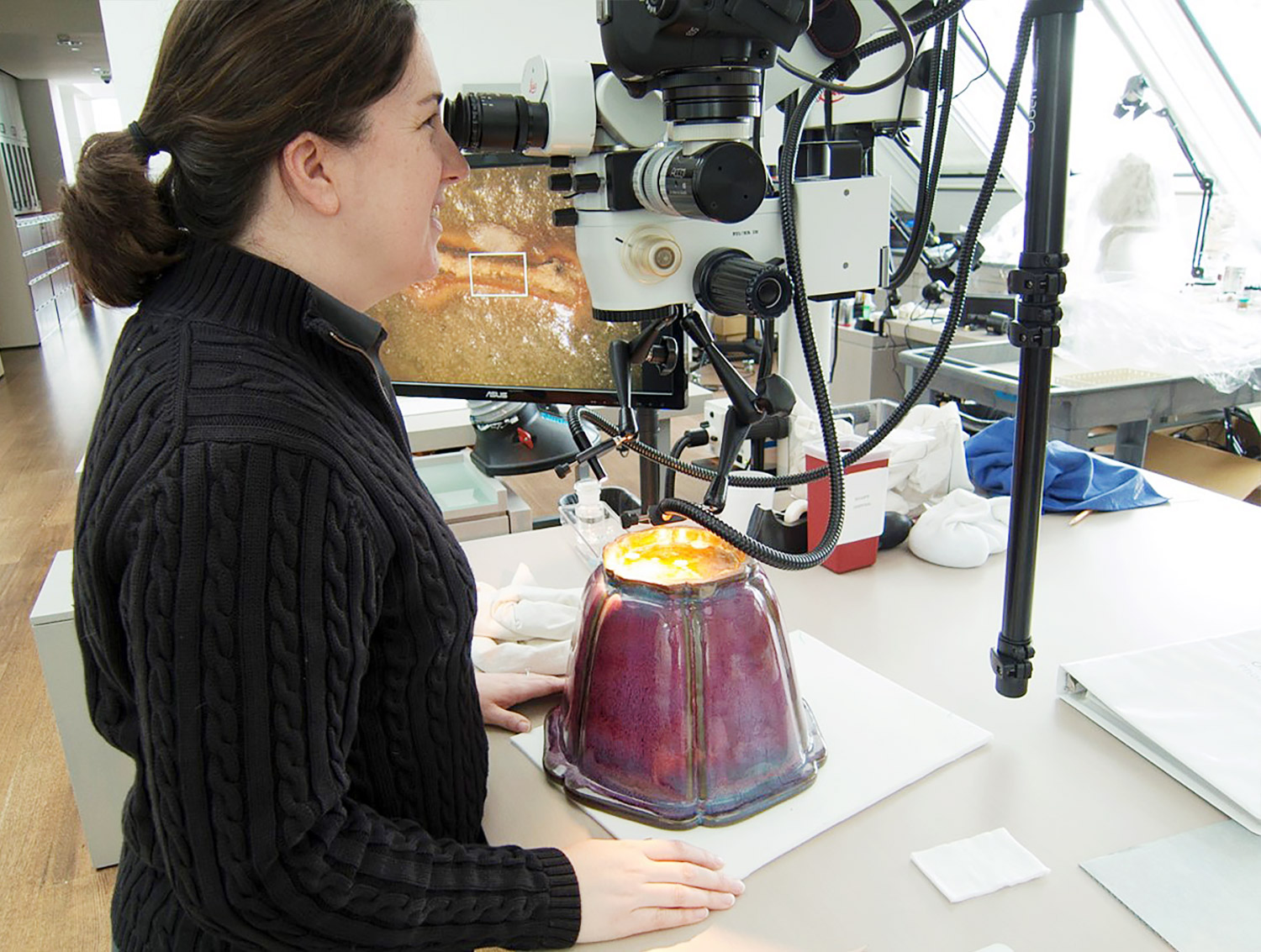

In hopes of finding hints about construction methods, Susan Costello and Lucy Cooper took X-radiographs of all of the vessels in our collection. They reviewed the results with Kathy King to identify patterns that reflected how the clay was worked and joined together.

For certain shapes of pots, the team found evidence that the clay was wheel-thrown in one piece with no joins. Other shapes seemed to have been made in a mold by pressing in slabs of clay. Still others appeared to have been initially wheel-thrown but then compressed in a mold.

King tested various theories firsthand, making her own reproductions by wheel-throwing, molding, and combining both approaches. After she completed her own re-created forms, the group X-rayed them so that they could compare the X-rays with those of the original Jun ware. Studying the two sets of X-rays was instructive.

“We were able to examine the behavior of the clay beyond observation of the object—we could identify stretching of the clay and clues to how aspects of the pot may have been attached, among other aspects,” King said.

X-rays were helpful in other ways as well, revealing or clarifying evidence of past restorations to the vessels, such as staples that were added centuries ago.

Complicated Glaze Studies

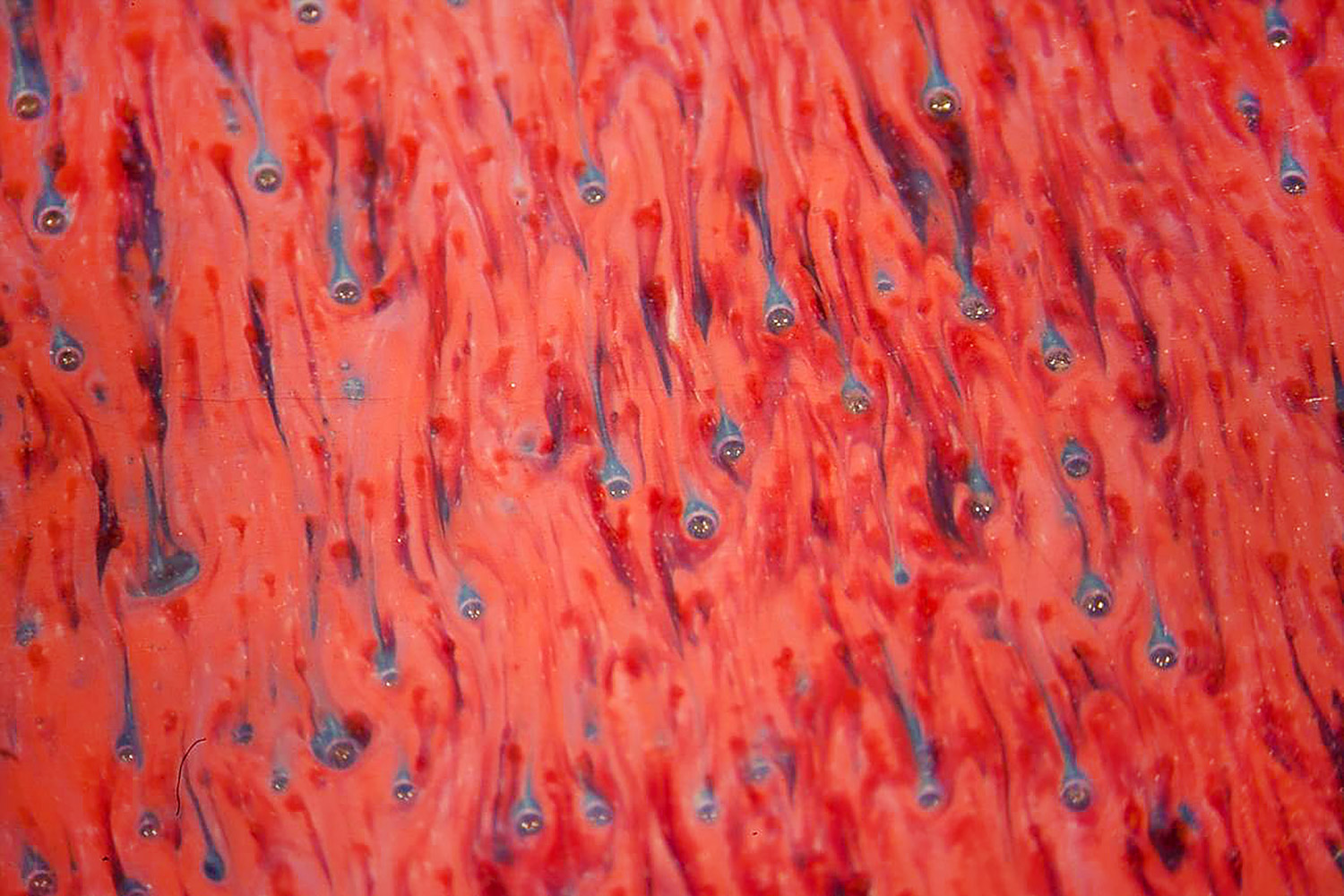

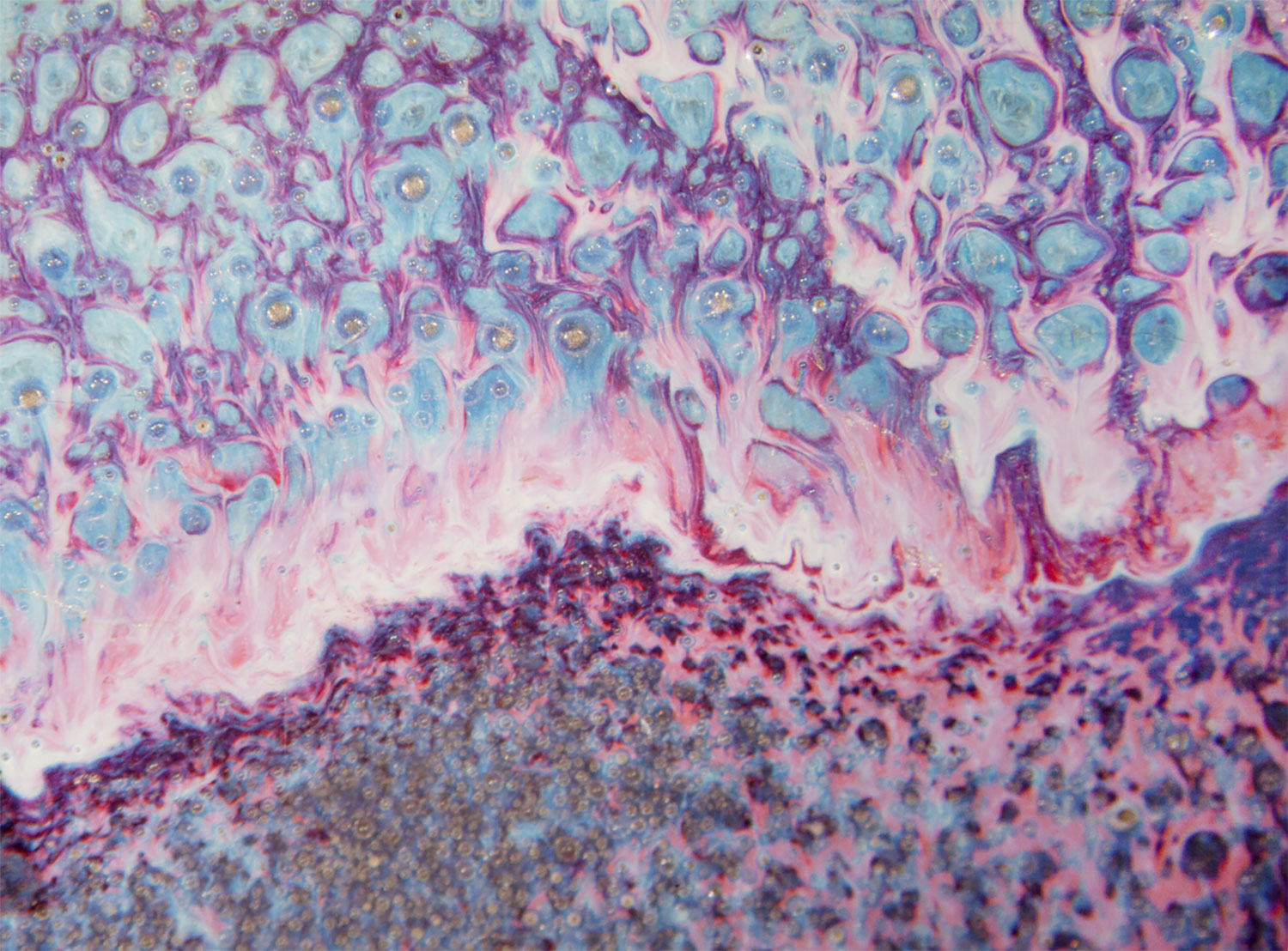

Studying the glaze chemistry was the next step. Previous research on traditional and splashed Jun ware glazes found that their blue hue is not due to the addition of a typical colorant such as cobalt or copper, as might be expected. Instead, the blue is principally a structural color resulting from an optical effect called Rayleigh scattering. This causes the vessels to appear blue when in fact, a sliver of the glaze held up to sunlight would actually seem yellowish.

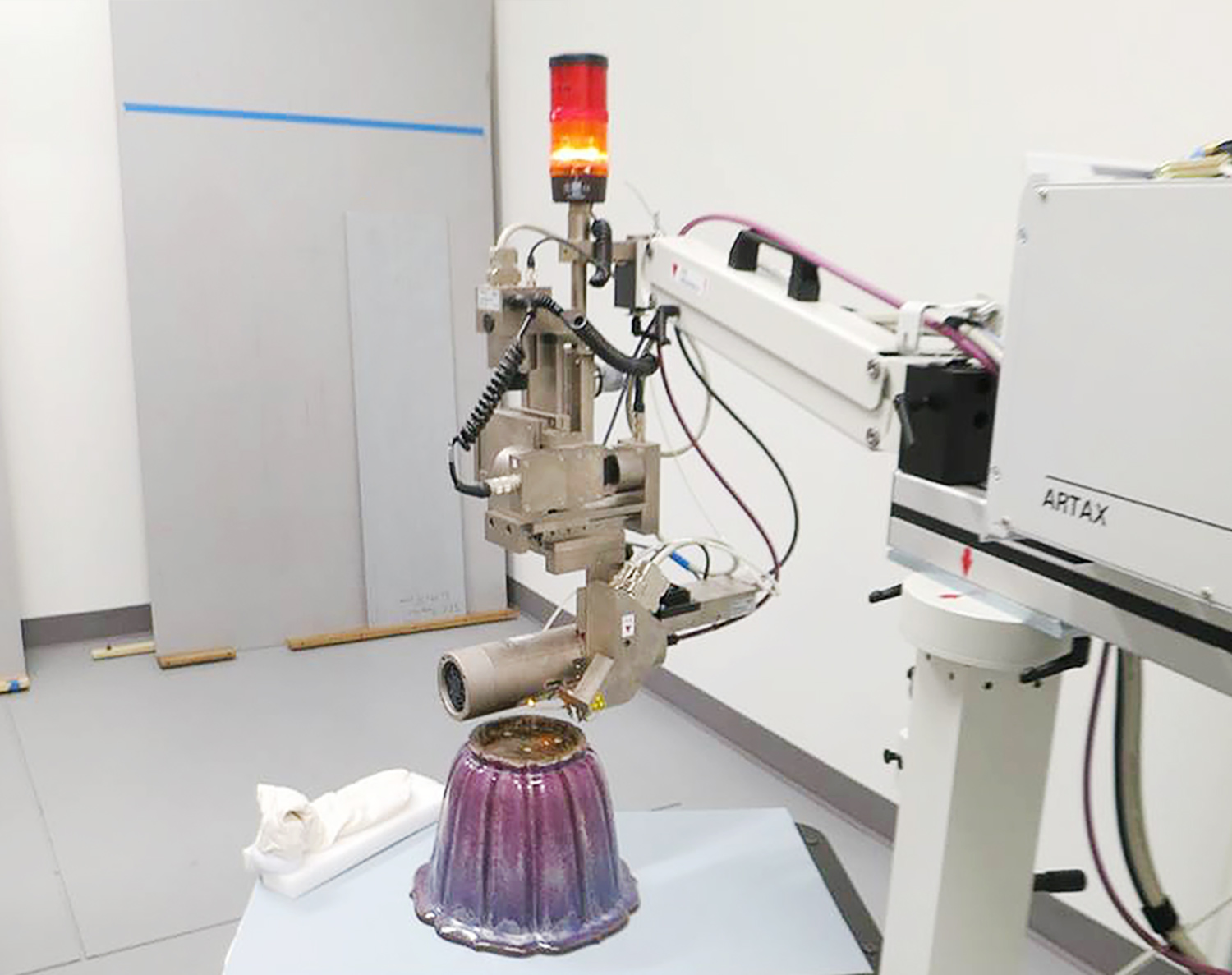

Costello and Cooper extracted tiny samples from 12 different Jun wares and studied the chemicals contained in each sample. They were surprised to find that similar amounts of copper, lead, and tin were in both red and blue glazes of purple numbered Jun pieces, even though the hues appear so dramatically different on the vessels. They also confirmed their assumption that the apparent mixture of the two creates the opalescent purple for which “splashed” and numbered Jun ware are known. Further investigation with even more powerful equipment is needed to identify the specific ratios of colorants in each type of glaze.

King has helped the group think about technical factors such as how the glaze was applied.

“We know copper is the colorant producing much of the color in the glaze, but how was that copper introduced?” King said. “Was it brushed on in a certain way beneath or on top of another glaze?”

The kiln firing and atmosphere also greatly influences the glaze. It may be particularly difficult to replicate these conditions—which were very different from modern-day techniques and equipment—but King said the team will continue to test glaze materials and firing methods at the Harvard Ceramics Studio.

Though the project has prompted many new questions, it has been an exciting experience for each team member. In fact, Cooper said she’s enjoyed that answers have not been easy to come by. “From a materials science perspective, this has been such a fascinating, illuminating project.”

Ultimately, the research will enhance knowledge and understanding not only of the museums’ numbered Jun ware, but of such objects in collections around the world. As King said, this type of work “gives another layer of information in appreciating the objects’ beauty.”