Works of art invite viewers to travel vicariously—into realms of the imagination, or to distant lands—whether for study or leisure. Our collections offer countless opportunities to explore unknown worlds.

Because most travel is currently canceled or suspended, curatorial colleagues are highlighting treasured works across the collections that have the power to propel viewers to different places and transcend boundaries. In the following, we meet kings, sages, scholars, tourists, and artists and collectors who expanded their horizons—and ours.

Have Throne, Will Travel

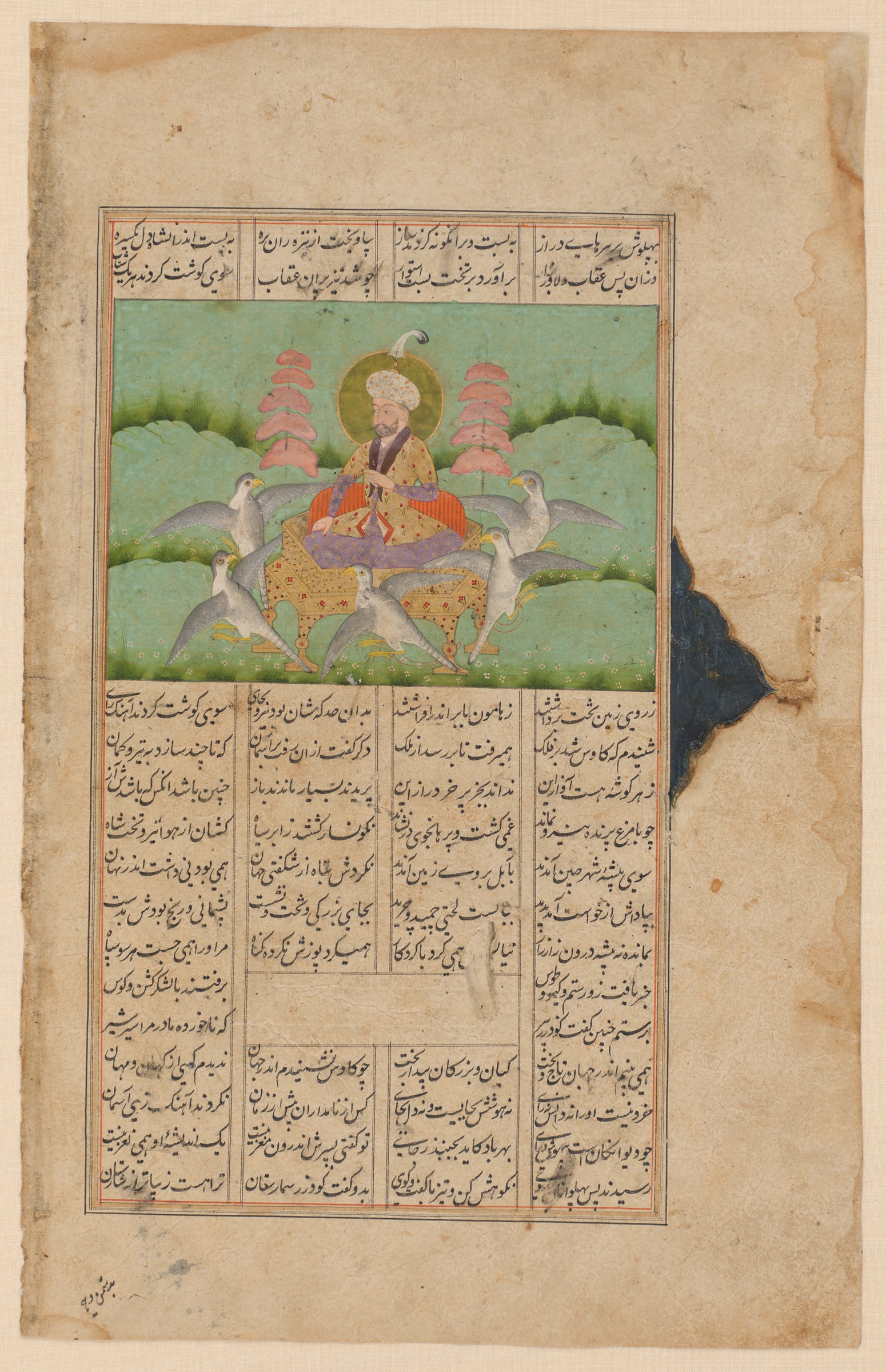

People’s desire for flying freely in the skies has a long history. In the Shahnama(Book of Kings), the Iranian national epic composed around 1010, we are told of an adventurous king in ancient Persia who wished to fly to the heavens. A Kashmiri copy of the Shahnama from the late 17th to early 18th century depicts the initial moments of this exciting journey.

King Kay Kavus is pictured above with a glorious halo around his head representing the divine power (farrah) bestowed on him. The Demon of Rage seduced Kay Kavus by praising his divine splendor and encouraged him to rule the world from the heavens. The idea tempted the king, so he devised an ingenious scheme: he tied each corner of his golden, jewel-studded throne to the feet of an eagle and set up large skewers with chunks of succulent meat just beyond the birds’ reach. As the hungry eagles fluttered hard to get to the meat, the throne took off. Eventually, though, the birds grew tired, sending both throne and king plummeting to the earth.

Luckily for the king, the Persian hero Rustam came to the rescue. This incident is one of many stories of Kay Kavus’s unbridled desires and foolish decisions, which invariably resulted in adversity for himself and his people.

Shiva Mihan, Schroeder Curatorial Fellow of Islamic Art, Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art