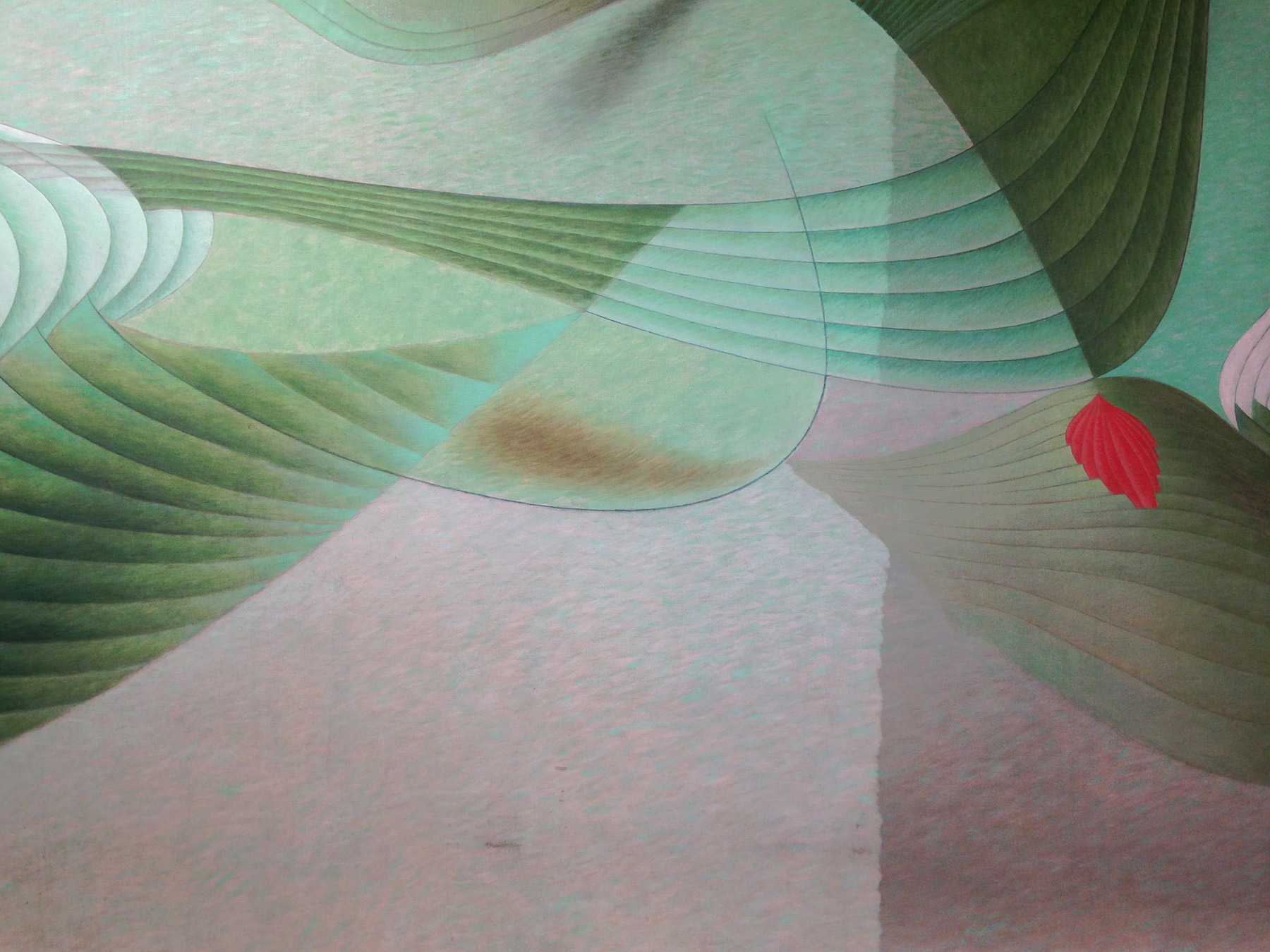

With its vibrant palette and wave-like forms, Herbert Bayer’s Verdure seems to beckon visitors to enter the galleries. And at 20 feet wide by 6 feet tall, it’s undeniably the largest work in our latest special exhibition, The Bauhaus and Harvard.

Completed in 1950, Verdure was commissioned for the dining room at Harkness Commons, in the Harvard Graduate Center. That space—now known as the Caspersen Student Center at the Harvard Law School—was part of a greater vision. Bauhaus founder and Harvard architecture professor Walter Gropius worked with his firm The Architects Collaborative to “bring together modern architecture, design, and contemporary art in one space,” said Laura Muir, research curator for academic and public programs and curator of The Bauhaus and Harvard.

Verdure was just one of several works that served as a backdrop (literally) to student life at the graduate center over the second half of the 20th century. Joan Miró, Hans Arp, Josef Albers, and Richard Lippold also contributed notable works to the site, which was celebrated for being the first example of modern architecture built on Harvard’s historic campus.