Eliot F. Noyes (1910–1977) is best known for being one of the Harvard Five, a group of modernist architects based in New Canaan, Connecticut, and for designing such iconic products as IBM’s Selectric typewriter. However, few know he had a brief yet important stint as an archaeologist. In 1935, he took leave from his studies at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design to join an expedition to the site of Persepolis in Iran, where he served as an architectural specialist and draftsman. While there he also painted a number of watercolors illustrating the sculptural reliefs at the site. Two of these paintings (as well as examples of reliefs) are now on display at the Harvard Art Museums, in the ancient Near Eastern art gallery.

Persepolis was the capital of the Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550–330 BCE), which at one time controlled a territory stretching from India to Egypt. In the late sixth century BCE, King Darius I founded Persepolis and began construction of a great palace complex decorated with extensive sculptural reliefs. His successors continued and expanded the construction of the palace, which was later burned in 330 BCE during the sojourn of Alexander the Great, under circumstances that continue to be debated.

Among the watercolors that Noyes painted while at Persepolis were reliefs from the facade of the Apadana, a large audience hall. One painting shows a Scythian in a pointed hat being led by a Persian usher; that he is being led by the hand, and is wearing a sword, suggests that the Scythian is a visitor to the palace, not a captive. Such depictions of Scythians, who lived around the Black Sea and on the Central Asian steppe, would have emphasized the vast reach of the Persian Empire and would have represented the empire as a cooperative enterprise (though conquest certainly played an important role as well; there are reliefs in our collections portraying soldiers at Persepolis).

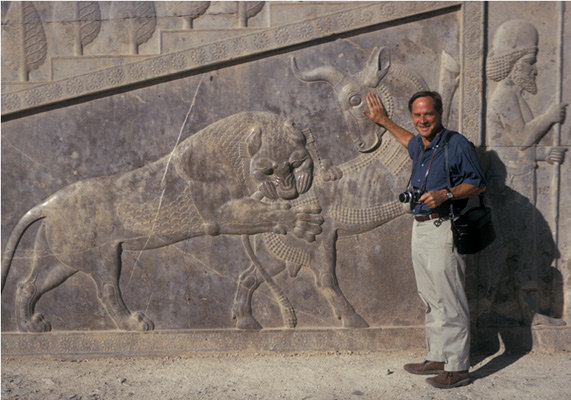

The other painting is of a relief showing a lion attacking a bull. Noyes faithfully recorded every detail—down to the seam between the two stone blocks from which the relief was carved and the chip in the lion’s mane—suggesting that he regarded these paintings as documentary in nature. The combination of these two animals, symbols of ferocity and strength in the ancient Near East, offers a succinct statement about the empire’s power, one that is repeated several times at Persepolis. It was designed to awe and impress visitors to the city. Certainly it impressed Noyes, who wrote to his father: “The sculpture, and there is a wealth of it as fresh as if carved yesterday, is the most extraordinary stuff I have seen in years.”

Henry Colburn served as curatorial fellow in ancient art at the Harvard Art Museums during the 2014–15 academic year. He is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Getty Villa, in Los Angeles.

To learn more about Noyes’s watercolors and the sculptural decoration of the palaces at Persepolis, join us for a gallery talk by Susanne Ebbinghaus, the George M.A. Hanfmann Curator of Ancient Art, on Thursday, December 17, from 12:30 to 1pm.