In his 19-part installation Folding, Refraction, Touch—Installation for the Busch-Reisinger Museum(2013), contemporary German artist Wolfgang Tillmans reflects on the medium of photography, the creation of photographs, and photographs as objects. The installation features images from throughout Tillmans’s career and includes a variety of subjects as well as abstract pictures. Highlighting Tillmans’s enduring interest in concepts of light, surface, abstraction, and the body, the installation is featured in the exhibition Folding, Refraction, Touch: Modern and Contemporary Art in Dialogue with Wolfgang Tillmans alongside 10 works by other artists, such as Oskar Nerlinger, Norbert Kricke, and Isa Genzken.

Tillmans, who divides his time between the United Kingdom and Germany, spoke with us recently by phone and shared insights about his installation.

How did you decide which images to include in your installation?

This isn’t a thesis piece—it doesn’t have a literal narrative that can be explained from A to Z. Very early on, I became interested in thematizing the object of the photograph, as well as our relationship to surfaces, to the visual world as we experience it through our eyes, in both a sensual and conceptual way. It is very much about being in the world as people, as bodies, covered in textiles and skin; there’s a membrane between our inner selves and the outer world.

Your installations are often attached to the wall in varied ways: some works are framed and others are mounted using tape or clips. Why do you use that approach?

It may initially seem endlessly varied, but in fact it’s not. There is a very distinct and strict number of techniques that I use to bring pictures to the wall. But they have developed over time.

I arrived at the taping method in the early ’90s, not so much from wanting to emulate or create a grunge, slacker, or low-tech aesthetic, but actually from a sense of purity. The photograph that came out of the processing machine always had a very specific and perfect allure to me as an object: this sheet of paper as it comes out is perfect as it is, so how can I show that to other people without destroying it, without endangering it, but also without obscuring or hiding its object-ness behind a mask by mounting or framing it? I found a way of taping the print so that no adhesive touches the front of the emulsion, but so it’s also easily removable from behind. It really came from a minimalist, purist approach, but it also allows one to experience the immediacy [of the object]. It is akin to the appearance of a teenager’s room, or of a note board where we rearrange things as we like to see them.

Tell us about the title of the installation. Did you think of it before you created it?

That came afterward. Sometimes it’s not so clear where it’s heading, but [in this case, the themes] became excitingly interconnected—objects and sensuality and surface and texture and concept and visual pleasure—they all connected around these words. And like a child who needs a name, [Folding, Refraction, Touch] suddenly seemed a good one.

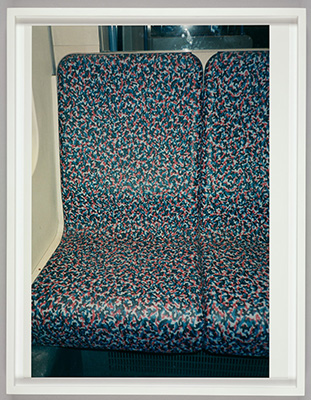

The fourth aspect [of the title, Installation for the Busch-Reisinger Museum] is a nod to the fact that it is at the Busch-Reisinger Museum, which is dedicated to the art of German-speaking countries. And it is [evident by my] inclusion of the small photographs with German subject matter, like the 1991 photograph of a classroom in my old school [Klassenraum, Leibniz Gymnasium I]; a 1992 picture of the Berlin Love Parade (Love Parade, rain); and the 1995 photograph of a Berlin subway seat, which is in an anti-graffiti pattern (U-Bahn sitz).

It’s interesting that some of these photos have an autobiographical element to them—such as your old classroom. Is that a takeaway you’d like viewers to have?

It would be strange if I would assume or expect the fact that this was my classroom to be of meaning to the viewer. Because that’s never my approach to photography. I don’t want to say, “Look, this is my classroom.” I want to say, “Look this is a classroom, seen through the eyes of someone who has a certain emotional relationship to and distance from that.”

This is really my photographic vision and it is completely counter to the social media views of photography showing everyday items and places. In social media, it is about, “Look, I have eaten this meal,” or, “This is me doing this.” Whereas for me it’s always been, “This is a pair of sports pants that can be imbued with different readings. They could be erotically charged. They could be looked at as a genre painting of drapery or as a fetish object.” I don’t want to say, “Look, these are my pants.”

But on the other hand, I use the first ability of photography—that we can relate to it—as a strength. What I hope is that people, through the low threshold of the medium, through its accessibility, and by me presenting it as something easily accessible, can actually connect to their own experiences and sentiments.