Some 200 years after it was largely forgotten, Harvard’s Philosophy Chamber—an 18th-century room that held art, scientific instruments, natural specimens, and curios collected from around the world—is once again springing back to life with the opening of the Harvard Art Museums exhibition The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766–1820 (May 19–December 31, 2017). A new book about the Philosophy Chamber promises to bring even more attention to this eclectic assemblage.

“It’s the catalogue this collection never had,” said Ethan Lasser, head of the museums’ Division of European and American Art and the Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American Art. Lasser organized the exhibition and edited the volume.

With the same name as the exhibition, the book covers an array of topics, including art history, the history of collecting, the history of science, early American culture, politics, and race. Nearly every object in the exhibition (of which there are more than 100) is displayed as a color plate, and accompanying essays explore the objects’ history and significance.

Original Scholarship

Plans for the book began years ago, when Lasser and others were carrying out their initial research, such as investigating early 19th-century skull drawings, enigmatic marble squares, the tracings on paper of mysterious inscriptions on Dighton Rock in Berkley, Massachusetts, and the layout of the Philosophy Chamber in Harvard Hall. The book is divided into three main sections, with essays by professors, curators, conservators, and advanced graduate students—largely drawn from a course about the Philosophy Chamber taught by Lasser and Jennifer Roberts, the Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities, and herself a contributor to the catalogue.

Part One, “Frameworks,” features introductory essays describing the Philosophy Chamber’s origins, functions, and eventual dispersal, as well as the socioeconomic and political contexts on both sides of the Atlantic that allowed for its development. The section also contains 72 color plates of the objects in the exhibition that were once housed in the Philosophy Chamber (or stand-ins for those that could not be located or were unavailable for loan). The objects are presented according to the order in which they were added to the chamber’s collection, largely in the form of donations.

Part Two, “The Collection,” features five thematic essays, each focused on three objects. Roberts, for example, considers the theme of submergence in her examination of Cartesian divers, small figures named for Descartes that were used to test buoyancy by placing them in water; a 1768 rendering, by Harvard professor Stephen Sewall, of the coastal Dighton Rock inscriptions; and The Dipping of Achilles, a Wedgwood medallion depicting a mythological moment of submergence. This theme and the four others—smoke, transposition, flatness, and decay—are explored as “gravities or magnetisms of association that drew the collections together in their historical moment,” as Roberts explains in her essay. Ultimately, “thematic groupings . . . do a better job of illuminating the period significance of those objects than do modern museological taxonomies.”

The last section, “Technical Studies,” details conservators’ recent findings on the materiality and history of select objects. Portraits by John Singleton Copley, a bust that Benjamin Franklin gave to Harvard, and Sewall’s work with Dighton Rock are all examined through scientific and analytical lenses. Rounding out the catalogue is an illustrated chronology that charts important moments in the life of the Philosophy Chamber, alongside relevant milestones in the broader histories of art, politics, and collecting.

The book is a “great example of the unique process that Ethan set up, where different aspects of the project and the museums’ resources could interact with each other,” said Aleksandr Bierig, a Harvard Ph.D. student in architectural and urban history. His essay “Transposition,” about objects in the Philosophy Chamber collection that enabled or emphasized shifts in scale (such as the microscope), is included in Part Two of the catalogue. Originally written for Lasser and Roberts’s class, Bierig’s essay incorporated research by conservators from the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies about the complicated creation of a Copley portrait. “It was really amazing to have conversations with the conservators and to try to relate my work to the discoveries they were making in the course of preparing for the exhibition,” Bierig said.

Editorial and Creative Contributions

As with all of the museums’ major publications, the book’s essays benefited from a dual internal and external review process before being prepared for editing. Managing editor Micah Buis and assistant editor Sarah Kuschner spent about four months copyediting the text and nearly the same amount of time working through the proofreading.

“The interdisciplinary and interconnected nature of the Philosophy Chamber called for a collaborative book editing process,” Kuschner said. “Since many of the key objects can be—and were—approached from different angles, we were frequently cross-referencing information from contributors and keeping those lines of communication open.”

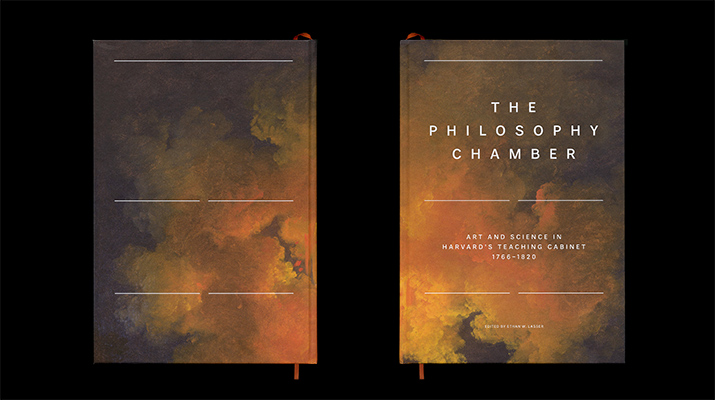

As the editing process unfolded, the museums’ design team worked to come up with an aesthetic that would fit not only the content of the book, but also the overall vision for the project. Guided by design manager Zak Jensen, the team researched 18th-century printing and the layout of period sources such as encyclopedias. “These references informed our layout and typography,” Jensen said. “At the same time, we wanted to keep in line with the contemporary visual approach we bring to all our publications.”

Inspiration also came from the shape of the Philosophy Chamber itself. In fact, the book’s dimensions are scaled down in proportion to the dimensions of the chamber, the cover layout is graphically modelled on the original floor plan, and the grid that underlies the interior page design also derives from the floor plan. The book’s inside front and back covers are two 1767 drawings of Harvard Hall (where the Philosophy Chamber was located) by Pierre du Simitière, effectively situating the book within the room’s physical parameters.

“The direct relationship between the book’s design and the original Philosophy Chamber is unique,” Jensen said. “We don’t often have the opportunity to make such a direct connection, and that makes this book special.”

The catalogue, printed by Die Keure, in Belgium, is available in the museums shop. It will be distributed for the Harvard Art Museums by Yale University Press.